This essay takes

the work of queer artist Dew Kim, participating in the Focus Asia

section of Frieze Seoul 2025, as a starting point to examine how queer

discourse is taking root in the Korean contemporary art scene. A fuller

discussion will follow in future writings that address the critical discourses

shaping 21st-century Korean contemporary art.

1. What Is

Queer?

The term ‘queer’

originally meant strange or abnormal. In the late 20th century, LGBTQ movements

reclaimed it as a term of self-identification, while academia witnessed the

emergence of Queer Theory, exemplified by Judith Butler’s notion of gender

performativity.

Today, in the art

world, queer does not simply mean art by or about sexual minorities. It exposes

and disrupts the arrangements of power, norms, and desire, functioning as a

methodology for rewriting social language through art. In the 21st century,

queer has evolved beyond a marker of identity into a deconstructive language of

norms. It has become one of the most radical tools for exposing the

contradictions that social orders and institutions conceal.

2. Dew Kim:

The Intersection of Desire and Taboo

At Frieze Seoul

2025, Dew Kim’s work presents queer not as a statement of sexual orientation

but as a device for visualizing cultural power structures. He juxtaposes

the moral authority of Christianity with the taboos and politics of pleasure

embodied in BDSM.

Dew Kim at Jeoldusan Martyrs’ Shrine, Seoul / Screenshot from Frieze

YouTube

Dew Kim at Jeoldusan Martyrs’ Shrine, Seoul / Screenshot from Frieze

YouTube

His installations

combine glittering ornaments, fragmented body parts, crucifixes and chalices,

and BDSM paraphernalia such as leather belts and whips. This excess of imagery

is more than provocation: it compels the viewer to sense how Korean society

manages the simultaneous operations of desire and discipline.

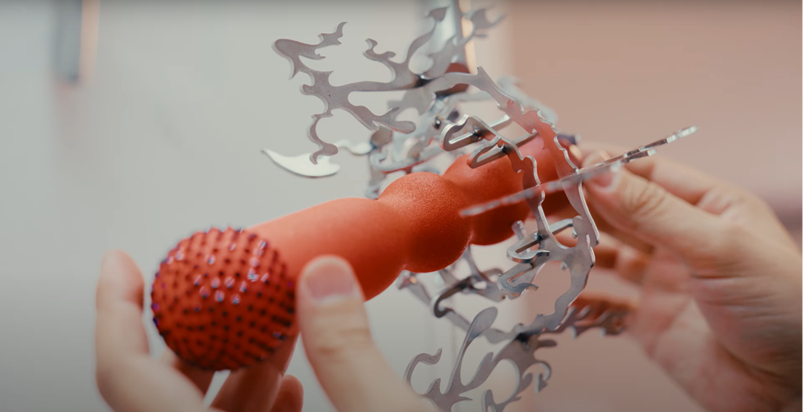

Work by Dew Kim / Screenshot from Frieze official YouTube

Work by Dew Kim / Screenshot from Frieze official YouTube

In a society

where religious ethics and family-based norms remain powerful, popular culture

may appear liberating but often internalizes uniform codes. Dew Kim visualizes

these tensions, revealing psychic landscapes where pleasure and sanctity, sin

and taboo coexist.

Performance by Dew Kim / Screenshot from Frieze official YouTube

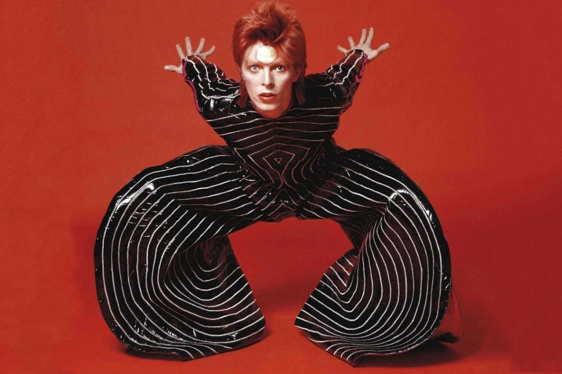

David Bowie, British pop musician

His strategy

resonates with David Bowie’s gender-bending performances that unsettled

pop-cultural norms, and with Félix González-Torres’s installations that brought

private love and public politics into the exhibition space. Dew Kim positions

queer not as a symbol of identity but as an aesthetic mechanism that twists and

redistributes social power.

3. Kim Jaeseok

and X-Large: Reading the Queer Strata of the City

Kim Jaeseok,

director of X-Large, extends queer discourse beyond gallery walls into the

fabric of the city. His tours of the Jongno and Euljiro districts reveal them

not merely as neighborhoods but as layers of Korean queer cultural history.

Director Kim Jaeseok and the space X-Large / Screenshot from Frieze

official YouTube

Director Kim Jaeseok and the space X-Large / Screenshot from Frieze

official YouTube

X-Large is a

domestic house in Gahoe-dong converted into an exhibition space. Visitors

remove their shoes to enter; admission is limited to four people at a time; the

space operates Wednesday to Saturday, noon to 6 p.m., strictly by reservation.

This intimate

setting creates a radically different experience from large museums or

commercial galleries. Encountering art in a space akin to a private home,

audiences experience it through everyday and bodily sensibilities rather than

institutional authority.

Kim Jaeseok (left) and the organizers of “Water and Space” (right) /

Screenshot from Frieze official YouTube

Kim Jaeseok (left) and the organizers of “Water and Space” (right) /

Screenshot from Frieze official YouTube

This approach

reveals queer discourse outside institutional records. X-Large links with the

historical traces of Jongno and Euljiro, functioning as a site that

activates local memory.

It recalls global

precedents where queer communities and art forged spatial identities—Christopher

Street in New York, Schöneberg-Nollendorfplatz and Kreuzberg in Berlin, Zona

Rosa and Roma in Mexico City.

4. The

Multilayered Perspectives of Global Queer

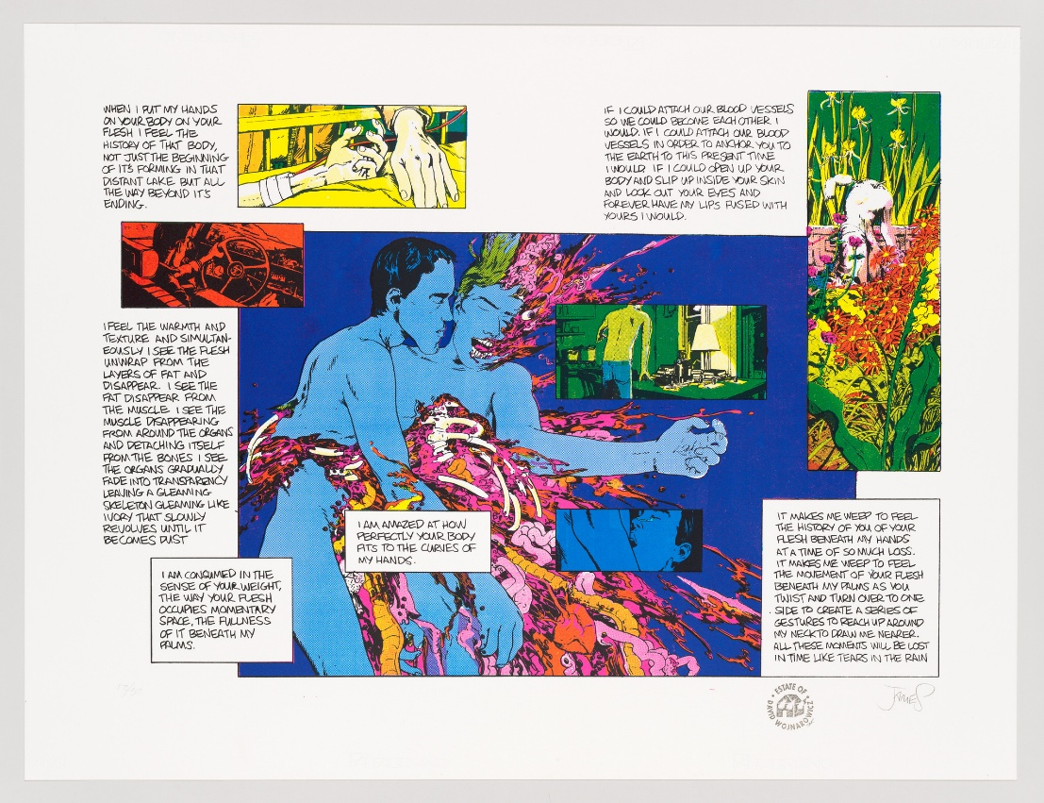

In the AIDS

crisis of the 1980s and ’90s, artists such as Félix González-Torres and David

Wojnarowicz transformed queer art from a representation of identity into a

language of political survival.

David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, Untitled,

1993 / Photo: Whitney Museum of American Art

David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger, Untitled,

1993 / Photo: Whitney Museum of American Art

In Berlin and

London, queer feminism intersected with postcolonial theory, leading to

exhibitions that examined migration, gender, and race together. In Santiago,

Mexico City, and São Paulo, queer art directly confronted religious taboos and

political repression, manifesting a distinct regional radicalism.

Shimura Takako’s 『Wandering Son』: a sophisticated masterpiece from Japan’s most prominent creator of

LGBT manga / Image: Amazon

Shimura Takako’s 『Wandering Son』: a sophisticated masterpiece from Japan’s most prominent creator of

LGBT manga / Image: Amazon

In East Asia,

diverse experiments also emerged. In Japan, Shimura Takako’s manga 『Wandering Son』 (Hourou Musuko) addressed

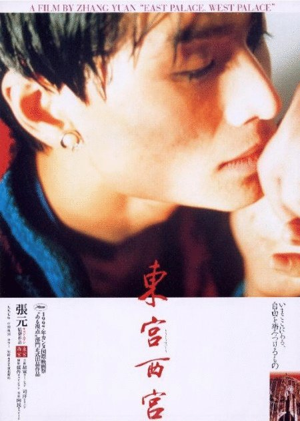

transgender identity and adolescent gender experience. In China, Zhang Yuan’s “East

Palace, West Palace” (1996) is regarded as the first feature film from

mainland China centered on homosexuality.

Poster for Zhang Yuan’s film “East Palace, West Palace” (1996)

In Taiwan, the Taiwan

International Queer Film Festival, launched in 2014, provided an

institutional foundation for queer culture, encompassing art, film, and

performance.

Queer discourse

in Seoul aligns with these global developments while bearing distinct tensions.

Korean society’s entrenched family-centered norms and religious authority make

queer art not just a cultural expression but a force that exposes structural

fissures. Recent developments—Frieze Seoul’s programming that foregrounds queer

perspectives, independent queer festivals, and university museums’ gender

archive exhibitions—position Seoul as a vital Asian context for queer art.

5. What Does

Queer Subvert?

Judith Butler

argued that gender is not innate but the performative result of repeated acts.

Queer art thus treats identity not as essence but as a deconstructable

language, exposing the operations of norms.

José Esteban Muñoz

described queer not as a fixed present identity but as a horizon of futurity—art

as a space for imagining communities that have yet to come. After Jean-François

Lyotard’s pronouncement of the “end of grand narratives,” queer emerges as a

minor language that destabilizes grand discourses and expands institutional

ruptures.

Together, these

theories frame queer art not merely as a tool for visibility but as a political

act of rewriting language, power, institutions, and space.

6. Queer

Discourse in Seoul’s Global Era

Seoul is one of

the fastest-growing art scenes in Asia, yet it remains a society where

conservative norms are strongly operative. The global success of Korean

cultural industries is predicated on uniform image production, while

family-centric and religious authority within society suppress diversity.

Within this

tension, queer art disrupts both. It fractures the homogenizing tendencies of

international industry while giving voice to those silenced by local structures

of repression. By mobilizing urban strata in neighborhoods like Jongno and

Euljiro, queer art rewrites the city’s sensory and cultural script, positioning

Seoul as a key site for global queer discourse.

The question “What

is queer?” does not demand a definitive answer. Queer is a perpetual question,

an ongoing process of unsettling and rewriting boundaries.

Queer is not

confined to the identity of sexual minorities. It is a language for rereading

the city, art, power, and the world—linking to global queer experiments while

generating a uniquely Korean tension. Ultimately, queer stands today as the

most intimate yet precise of positions: a core language of 21st-century global

art.

References

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (1990), Bodies That Matter (1993)

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia (2009)

- Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition (1979)

- Félix González-Torres, works including Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)

- David Wojnarowicz, works and activism during AIDS crisis (1980s–90s, New York)

- David Bowie, performances challenging gender norms (1970s–80s)

- Dew Kim, artist profile & Frieze Seoul 2025 program

- X Large Gallery (Seoul, Gaheo-dong), official visitor information

- Stonewall/Christopher Street, New York (LGBTQ+ rights history)

- Schöneberg–Nollendorfplatz & Kreuzberg, Berlin (queer culture districts)

- Zona Rosa & Roma, Mexico City (queer cultural hubs)

- Shimura Takako, Wandering Son (Hourou Musuko, 2002–2013)

- Zhang Yuan, East Palace, West Palace (1996, PRC queer cinema)

- Taiwan International Queer Film Festival (since 2014)