Jayoung Hong (b. 1995) explores how humans

have perceived nature and integrated it into systems of thought through various

forms of gardens and past modes of play. She focuses on the multiple

perspectives surrounding objects found in different eras, cultures, and in

nature itself, and by reflecting these fluid shifts and transformations of

perspective in her practice, she transforms the exhibition space into a site of

visual play.

Jayoung Hong, 12 Mountains 9 Stones 6 Liters of Water, 2020, Jesmonite, pvc, water, water pump, acrylic pipe, grass, clay, wood structure, telescope, Dimensions variable ©Jayoung Hong

Jayoung Hong began her practice with an

interest in the subjectivity that emerges when new aspects of an object are

discovered—or when the object itself is transformed—through the act of

prolonged observation. Just as looking functions as a crucial stage in her

working process, her resulting works not only highlight visual elements but

also actively invite the viewer’s own visual engagement and movement.

Jayoung Hong, Eyeholes for Bending: One of Peepject: Two Holes for Eyes x 3, 2020, Wood, jesmonite, nylon fishing line, plastic mesh, 120x30x25cm ©Jayoung Hong

To encourage visual movement, Hong pays

close attention to the “frame” that exists between the viewer and the object.

Here, the frame signifies not only an awareness of the act of looking itself,

but also everything that mediates it.

By weaving shifts of the frame into her

work, she enables the free transformation and movement of perspective, offering

multiple viewpoints. Through this, Hong hopes that viewers will follow these

perspectives with their eyes, while imagining new spaces and times within their

own minds—and finding pleasure in that process.

Jayoung Hong, Eyehole for Standing:One of Peepject: Two Holes for Eyes x 3, 2020, Wood, 90x120cm ©Jayoung Hong

Her experiments with shifting frames are

most evident in two representative strands of her practice: sculptures that

construct landscapes and sculptures with interiors. The first type employs a

frame set by the artist as a visual support, enabling viewers to gaze at a

landscape through an aperture, or reconfiguring elements taken from their

original sites into new, imagined sceneries.

For instance, the series ‘Peepject: Two

Holes for Eyes x 3’ (2018–2020) consists of objects that require viewers to

bend down or crouch in order to peer inside through small holes. By prompting

such physical gestures, the objects transform the exhibition space into a kind

of stage, where the audience becomes both the subject who looks and the

performer who enacts movement.

Jayoung Hong, Eyehole for Standing: One of Peepject: Two Holes for Eyes x 3, 2020, Wood, 90x120cm ©Jayoung Hong

Through this work, Hong explains that she

sought to address “the shifting relationship between subject and object in the

act of looking.” The viewer’s restricted field of vision becomes a “frame” that

draws them into the miniature world of objects, evoking new bodily sensations.

In this way, the apertures that invite

viewers to peer inside both limit their sight and, paradoxically, provoke a

more active visual engagement. They compel attention to places one would not

normally look and to objects that might otherwise be easily overlooked,

transforming casual glances into acts of exploration.

Jayoung Hong, Fantastic Rocks, 2022, larch plywood, pine wood rod, 100x90x32cm ©Jayoung Hong

In this way, Hong’s exploration of the

movement of gaze and body naturally led her to an interest in Eastern

philosophy and traditional East Asian painting, both of which embrace fluidity

that shifts according to perspective. Among these, she was particularly drawn

to sansuhwa (landscape painting), which captures not a literal reproduction of

scenery but the diverse viewpoints of the person beholding it.

In sansuhwa, multiple perspectives are

brought together within a single scene, reflecting the painter’s impressions of

various landscapes encountered while wandering through nature. The elongated

scroll format—whether horizontal or vertical—unfolds the painted landscape as

if it were a journey, inviting the viewer’s eyes to traverse the scenery as

though they were walking through the mountains themselves.

Installation view of 《Kak》 (HITE Collection, 2022) ©Jayoung Hong

In East Asian landscape painting, this act

of traveling with the eyes through an image is called wayu (臥遊), literally meaning “to wander while lying down.” First proposed by

the painter Zong Bing during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the concept

later developed through the painters of the Northern Song dynasty and became a

foundational principle of East Asian landscape art.

Influenced by this tradition of wayu—which

invites the viewer to journey through multiple perspectives, viewpoints, and

embedded ideas—Hong began to explore the possibilities of diverse ways of

seeing that have long been marginalized by the Western paradigm of

ocularcentrism, which seeks to frame the world from a single, fixed point of

view.

Jayoung Hong, Beyond Landscape, 2022, Birch plywood, wax, 100x90x2.4cm ©Jayoung Hong

Building on her interest in sansuhwa,

Beyond Landscape (2022) takes the form of a folding screen

made from wooden structures onto which Hong brushes wax to depict a landscape.

Unlike traditional ink landscapes, she employs wax as a material to create a

relief-like effect, positioning the landscape somewhere between two and three

dimensions.

Furthermore, by cutting holes into the

screen, the artist allows the scenery beyond the artwork to enter the viewer’s

line of sight. In this way, the viewer follows the painted landscape with their

eyes while simultaneously shifting perspective toward the actual surroundings

in which they stand.

Jayoung Hong, Sansu Sculpture, 2023, PLA print from 3D-scanned sand sculpture, 7.5~41x22~40x18~32cm(4) ©Jayoung Hong

Meanwhile, in Sansu

Sculpture (2023), Jayoung Hong reinterprets Fan Kuan’s Travelers

Among Mountains and Streams by translating it into three dimensions.

In the process of moving from the pictorial plane to a sculptural form, details

that did not exist in the original painting were newly imagined and created by

the artist.

Envisioning the unseen back, sides, and

even the interior of rocks, Hong carved sand with water as if painting a

landscape. Since sand sculptures cannot be preserved or transferred in their

original form, the work was reproduced as a three-dimensional object through 3D

scanning and printing technology.

Jayoung Hong, Sansu Sculpture, 2023, PLA print from 3D-scanned sand sculpture, 7.5~41x22~40x18~32cm(4) ©Jayoung Hong

The landscapes once seen by Fan Kuan are

reimagined through the eyes and mind of Jayoung Hong, and the resulting

three-dimensional Sansu Sculpture, layered with these

overlapping perspectives, is explored anew through the viewer’s gaze. As

audiences follow Hong’s landscapes with their eyes, they encounter smooth

surfaces alongside uneven, densely textured contours, experiencing a tactile

sense of “touching with the eyes.”

Supporting this work is Octagonal

Rock Pedestal (팔각괴석받침) (2023), modeled after

a rock pedestal at the site of Jagyeongjeon Hall in Changgyeonggung Palace.

Hong relocates this pedestal—now merely an everyday object beside a bench—into

her newly constructed landscape, drawing attention to details that had

previously gone unnoticed within the original scenery.

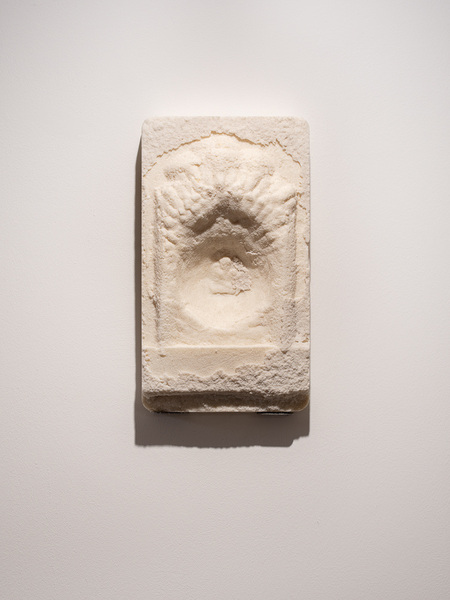

Jayoung Hong, Pillar Head 1, 2021, Wax, sand, 18x12.5x5cm (2ea) ©Jayoung Hong

In this way, her experiments with the

tactility of vision and the act of isolating overlooked elements from an

overall landscape to place them in new scenes also appear in her work

reproducing historical artifacts or elements of traditional ornamentation.

Jayoung Hong has recreated decorative

motifs found across various eras and cultures, including columns of traditional

architecture, ancient murals, and rock pedestals, transforming them into

sculptural forms. In the process, she selectively isolates and rearranges intricate

and ornate components, constructing entirely new compositions from these

elements.

Jayoung Hong, Buried Temple, 2022, Sand-scanned soy wax, 46.5x26.7x10cm ©Jayoung Hong

For example, architectural decorations such

as a fountain (Waterwall, 2021), a pillar head (Pillar

Head, 2021), and a façade (Temple Facade, 2021)

are transposed onto gallery walls like reliefs, creating entirely new

landscapes. While referencing the originals, these works are rendered using a

mix of sand and wax or gesso applied to sponge, emphasizing rough textures. The

delicate and ornate details produced with coarse materials evoke a tactile and

visual sensation distinct from the smoothness of the original works.

Jayoung Hong, Wall Fountain, 2022, Wax, sand, gravel, water, water pump, Styrofoam, MDF, 86x61x36cm ©Jayoung Hong

Hong reconstructs fleeting or easily

overlooked scenes discovered in every corner of a landscape, as well as objects

that span multiple eras and cultures, using fluid materials such as water,

sand, and wax. In her work, water embodies time while remaining unfixed,

offering a continuously flowing landscape.

For instance, she incorporates fountains as

part of a sculpture, drawing attention to the dynamic movement of water, or

allows viewers to trace landscapes reflected on the water’s surface. In the

previously discussed work Sansu Sculpture, mist and water

envelop the sculpture’s body, creating a scene in which they interact

organically.

Splashing droplets generate ripples on the

surface, which in turn form drops on the sculpture itself, while the swirling

mist continually wraps and moves around the sculpture, adding a sense of motion

to the otherwise stationary form.

Jayoung Hong, The Gate of Wind and Water, 2023-2024, Wax on ceramic tiles, 40x40cm (32), 160x160x40cm ©Jayoung Hong

Jayoung Hong also utilizes the material

qualities of wax, which becomes painterly when melted and sculptural when

solidified. For example, her large-scale door-shaped work The Gate of

Wind and Water (2023) draws inspiration from the blue-and-white

porcelain tradition found in both Eastern and Western cultures. She magnified

and reduced the forms of mountains, clouds, and water that make up the

landscape and applied them in wax onto tiles.

Inspired by the European practice of

decorating doors and walls with blue-and-white tiles, she installed twelve of

these works in the shape of a door, creating a landscape that unfolds beyond

them. In this work, the wax—applied on top of the tiles—is carved, layered, and

erased, producing various accidental effects and positioning the piece in an

intermediate space between painting and relief sculpture.

Jayoung Hong, Layered Tunnel(Glacier), 2024, Paraffin, 37×40×37cm ©Jayoung Hong

Since 2023, Hong has begun creating

“sculptures with interiors,” inspired by the concept of “architectural

sculpture” after reading books by first-generation American curator Lucy

Lippard. While conventional sculptures emphasize the exterior and conceal the

interior, architectural sculpture functions like a building, containing an

internal space and serving as a kind of shelter.

Hong regards caves, bowls, and shells as

prototypes for sculptures with interiors, and she incorporates these materials

into her work or creates ceramic pieces capable of holding something inside.

Jayoung Hong, Statue of Goddess from Water, 2023, Wire mesh, plaster bandages, Jesmonite, cuttlebone, seashells, stones, 40×25×28cm ©Jayoung Hong

For example, Statue of Goddess

from Water (2023), made from seashells, stones, and cuttlebone, is

based on the imagined discovery of a goddess statue from an ancient matriarchal

society beneath the sea.

She imagined what the form of a goddess

might have been if a society led and guided by women had persisted, and instead

of a vertical figure, she conceived the goddess as a natural form (mountain)

with an internal cavity, echoing a womb that nurtures life. Accordingly, she

created a structure of three overlapping mountain peaks containing space and

collaged materials found in nature onto them, imparting color and form.

Installation view of 《Winter Sculpture with Warming Vegetables》 (Gallery2, 2025) ©Gallery2

Building on this interest, recently Jayoung

Hong has been creating works that allow viewers to peer inside like a tunnel

while also seeing the landscape beyond the openings (the ‘Layers Tunnel’

series, 2024). She has continued to experiment with arranging sculptures to

form gardens (《Between Lying Columns》, Ponetive Space, 2024) and reconfiguring landscapes discovered in

the interaction between nature and humans from multiple sculptural viewpoints (《Winter Sculpture with Warming Vegetables》,

Gallery2, 2025).

Hong’s practice, which presents diverse

perspectives and viewpoints, awakens the sense of seeing through multiple

sensory channels in today’s environment, where everything is quickly observed

and forgotten, and embodies the dynamism of the act of looking. As she

describes herself, “a maker of playgrounds for the eyes,” her open-structured

sculptures guide the gaze inward while inviting the viewer to imagine beyond,

creating a new space for visual play.

“Through my creations, I want to offer

diverse perspectives. My goal is to unfold new spatiotemporal experiences in

each viewer’s mind through this process.” (Jayoung Hong, excerpted from a Daily Art

interview)

Artist Jayoung Hong ©Daily Art

Jayoung Hong graduated with a BFA in Fine

Arts from Korea National University of Arts. Her solo exhibitions include 《Winter Sculpture with Warming Vegetables》

(Gallery2, Seoul, 2025) and 《Between Lying Columns》 (Ponetive Space, Paju, 2024).

She has also participated in numerous group

exhibitions, including 《Correspondences》 (Shinhan Gallery, Seoul, 2024), 《Firsthand

Shop》 (CHAMBER, Seoul, 2024), 《Defragmentation》 (Mullae Art Space, Seoul, 2023), 《Peer to

Peer》 (SPACE ON 洙, Seoul,

2022), 《The…Saver》 (Audio

Visual Pavilion, Seoul, 2022), 《Kak》 (HITE Collection, Seoul, 2022), and 《Comma

to Comma》 (Seoul Community Cultural Center Seogyo,

Seoul, 2022).

In 2023, she was selected as a

7th-generation Open Studio artist at the Uijeongbu Art Library.