‘The Art

Newspaper’ (June

2, 2025) recently ran a cover story titled “Korean artists are taking the

world by storm.” The feature explores why contemporary Korean art is

resonating so strongly with international audiences. Following exhibitions in

cities like New York, London, Abu Dhabi, and Singapore, the article gathers

insights from curators and scholars to illustrate how this is not merely a

trend—but a structural shift in the art world.

Institutional

Recognition of Korean Artists

Central to the

article is the upcoming solo presentation of Ayoung Kim at MoMA PS1 in

New York, scheduled to run from November 6, 2025, to March 16, 2026.

Ayoung Kim’s

single-channel video, Delivery Dancer’s Sphere (2022),

explores South Korea’s gig economy; the artist will be the subject of a show at

MoMA PS1 (6 November-16 March 2026). Courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai

Ayoung Kim’s

single-channel video, Delivery Dancer’s Sphere (2022),

explores South Korea’s gig economy; the artist will be the subject of a show at

MoMA PS1 (6 November-16 March 2026). Courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai

The exhibition

showcases her single-channel video Delivery Dancer’s Sphere

(2022), which earned the 2025 LG Guggenheim Award. This work examines

South Korea's gig economy through a sensory narrative that investigates how

automation and labor structures influence both the physical body and emotional

life.

Do Ho Suh’s Rubbing/Loving

Project: Seoul Home (2013–22) is on show at Tate Modern in

London / © Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh’s Rubbing/Loving

Project: Seoul Home (2013–22) is on show at Tate Modern in

London / © Do Ho Suh

Meanwhile, across

the Atlantic, Do Ho Suh has been capturing attention with Seoul

Home (2013–22) on display at Tate Modern in London.

Simultaneously, Haegue Yang continues to gain international acclaim with

her conceptual and materially rich work, actively engaging audiences in both

Europe and the United States. In the article, Yang reflects,

“There are great

artists in Korea. There always have been. No matter what

circumstance—politically, socially, culturally—the artists are great.”

Beyond

"K-Art": Embracing Diversity and Complexity

‘The Art

Newspaper’

stresses that Korean contemporary art cannot be boxed into a single identity or

aesthetic category. While traditional mediums such as ink painting and the

abstraction of Dansaekhwa remain important, today’s Korean artists are

addressing layered themes—technology, gender, social dynamics, and historical

trauma—using deeply conceptual approaches.

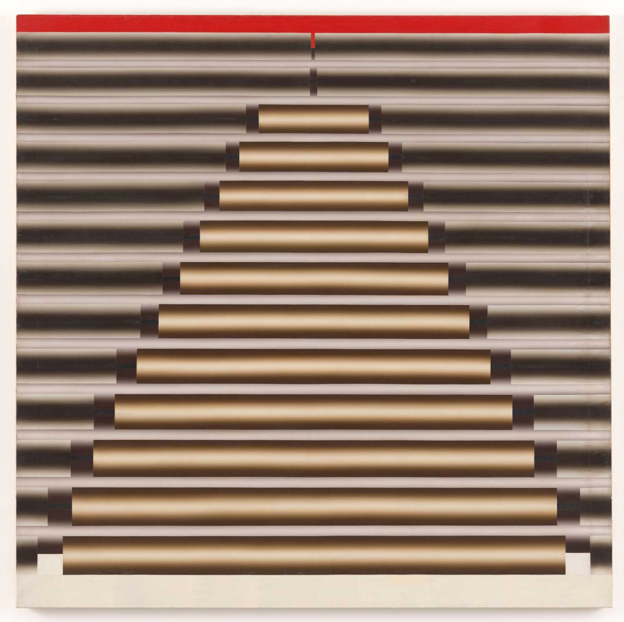

Nucleus

F-G-999 (1970) by Lee Seung Jio is in the collection of the Museum of Modern

Art in New York / © 2021 MoMA, New York

Nucleus

F-G-999 (1970) by Lee Seung Jio is in the collection of the Museum of Modern

Art in New York / © 2021 MoMA, New York

Artists like Lee

Bul and Mire Lee are reshaping narrative forms, focusing less on

national origin and more on personal, structural, and global conditions. Their

work reframes the Korean experience through a universal, contemplative lens.

Lee Bul’s Long

Tail Halo is the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Genesis

Facade Commission (until 10 June) / Photo: Eugenia Burnett Tinsley;

courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lee Bul’s Long

Tail Halo is the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Genesis

Facade Commission (until 10 June) / Photo: Eugenia Burnett Tinsley;

courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

Kyung‑Hwan Yeo, curator at the Seoul Museum of

Art, emphasizes that

“Since the 1990s,

Korean art has increasingly engaged with contemporaneity and plurality within

the overarching sociopolitical and cultural transformations of globalization.”

He explains that

this is not merely expansion in scope, but an internal restructuring of Korea’s

artistic ecosystem. The establishment of the Gwangju Biennale (1995), Busan

Biennale (1998), and Seoul Mediacity Biennale (2000) was followed by the

emergence of new institutions and experimental media practices. This

institutional groundwork has been bolstered by international galleries entering

Seoul and the launch of Frieze Seoul, positioning South Korea as a major

hub in the global art market.

Institutional

Interest, Collection, and Scholarship

This increasing

attention is reflected in museum acquisitions and academic research. In 2023,

the 《Only

the Young: Experimental Art in Korea 1960s–1970s》

exhibition, organized by Seoul’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

(MMCA) and later shown at the Guggenheim in New York and Hammer Museum in Los

Angeles, reintroduced Korean experimental artists into the global art

historical narrative.

Soojung Kang, a senior curator at MMCA and a

co-organizer of the show, observes:

“These artists were

already present within the fabric of global avant-garde art, but the exhibition

revealed their voices anew—reframing them as central to the broader

international discourse.”

Following the

exhibition, many involved artists have been featured in institutional

exhibitions, their works acquired by major collections, and scholarly attention

to Korea’s avant-garde practices has grown rapidly.

Koreanness as an

Ongoing Artistic Exploration

A key reason why

Korean art resonates globally is its engagement with complex historical and

cultural experiences—military dictatorship, division, rapid industrialization,

democratization, and the rise of technology-infused capitalism. These themes

are not reduced to national branding but explored with depth and nuance.

Curator Yeo adds,

“For most,

‘Koreanness’ is not a label to claim, but rather a deeply rooted artistic

preoccupation they have wrestled with over time.”

Korean aesthetics and identity are “continuously broken down and renewed within

Korea’s cultural, economic and social context.”

Jiwon Lee, curator at the Sharjah Art

Foundation, underscores that

“Substantial growth

of a scene is not about finding a universal language or watering down the

definitions but about being self-aware, providing access points and considering

space and time for translation.”

She continues:

“Given this, Korean

contemporary art can communicate a myriad of different themes, pulling from its

rather dramatic transformation in the past century—from being a previously

colonised and war‑ridden country to rising to a significant economic power in

the world, as well as the societal conflicts and unresolved discords that

derive from it.”

Shifting the

Question: From Expansion to Connection

In its conclusion, ‘The

Art Newspaper’ proposes that the crucial question facing Korean

contemporary art is no longer whether it can go global, but rather:

How will it

continue to connect?

This invites deeper

reflection on:

- What narrative

forms and languages Korean artists will adopt to dialogue with global art

discourse.

- Who will interpret

their stories, and from what critical perspectives.

- How local art

platforms can secure sustainable roles within the global ecosystem.

Korean contemporary

art has graduated from being a cultural trend to becoming a transformative

force reshaping the structure and narrative of global art. The pressing

question now is: How will we document, interpret, and sustain this ongoing

momentum?

This piece is

based on The

Art Newspaper (June 2, 2025) cover article titled “Korean artists are

taking the world by storm—but why does their work resonate so widely?”

Read

the full original : theartnewspaper.com