Kwak Intan (b. 1986) reconstructs remnants

of the past to document and express them as sculptures in the present. Drawing

inspiration from the paintings and sculptures of great masters in art history,

he transforms lingering afterimages from his mind into entirely new sculptural

creations of his own.

Installation view of 《The Realm of Three (3의 영역)》 (Oh!zemidong Gallery, 2016) ©Oh!zemidong Gallery

In his early works, Kwak Intan presented

figurative sculptures that seemed to externalize painful obsessions and

anxiety. For instance, in his first solo exhibition 《The

Realm of Three (3의 영역)》, his

works ranged from busts with grimacing expressions, to human figures standing

with their heads bowed and faces buried in chains, to small sculptures where

parts of the body were obsessively overlapped—each conveying psychological

states through the language of sculpture.

Kwak Intan, Gate – 1, 2019, Steel, Stainless steel, 213x120x113cm ©Museumhead. Photo: Junyong Cho

Meanwhile, since 2019, Kwak Intan’s work

has shown a shift away from the compulsive representation of figurative bodies

toward a tendency toward abstraction. From this point on, he began referencing

historical works described in art history as a way of gathering fragments

drifting through his mind and reconstructing them into sculptural forms.

Kwak drew inspiration from the sculptures

of Vladimir Tatlin and Auguste Rodin, as well as the paintings of Ha Chong-Hyun

and Lee Ungno, reinterpreting them into sculptures with his own forms,

structures, and textures. However, these historical references are intertwined

with the artist’s obsessions—that is, his confrontation with the inner

self—resulting in works that appear jumbled together, without adherence to any

fixed principle or style.

Installation view of 《Unique Form》 (studio 148, 2019) ©Kwak Intan

In his 2019 solo exhibition 《Unique Form》, where this tendency first

became apparent, Kwak dismantled and reconstructed earlier busts that had

expressed the psychology of obsession and freedom, layering them together with

new sculptures appropriated from the past. Art critic Choi Tae-man observed

that by appropriating historical references and then re-appropriating his own

past, Kwak created “a sculptural time-space in which history and the self

cannot be clearly distinguished.”

Installation view of 《Unique Form》 (studio 148, 2019) ©Kwak Intan

Within this hybridized time-space, the

artist’s own history becomes entangled with both Eastern and Western art

histories. Furthermore, his work dissolves and intermingles the boundaries

between painting and sculpture—traditional media with distinct hierarchies and

histories—repositioning them as new sculptural forms. The flowing materiality

of ink overlaps with the traces of welded steel fragments, merging ink painting

and sculpture, while resin and acrylic paint cling to structural frameworks,

bringing painting and sculpture together in a single place.

Kwak Intan,

Sculpture Gate: Development of the Head, 2020, Steel,

perforated plate, stainless steel, cement, plaster, resin, 52x80x80cm ©Kwak

Intan

Kwak Intan,

Sculpture Gate: Development of the Head, 2020, Steel,

perforated plate, stainless steel, cement, plaster, resin, 52x80x80cm ©Kwak

IntanMoreover, fragments of discarded materials

from the production process often mingle with the finished sculptures, blurring

even the boundary between the artwork (the sculpture as a result) and the

pedestal (the base that supports the sculpture and directs the viewer’s gaze).

In his practice, the pedestal and the sculpture are never fixed in their

positions. A sculpture once presented as an autonomous work may, on another

occasion, stand in the place of a pedestal.

Kwak Intan, The Out of Control of Compulsion, 2020, Steel, cement, resin, perforated mesh, stainless steel, 132×45×35cm ©Kwak Intan

In his 2020 solo exhibition 《Sculpture Gate》 at Space 9, the works

similarly revealed how various art historical references became entangled with

the artist’s own compulsions about sculpture, appearing sutured together within

the bodies of new sculptural forms.

For example, in the cubic sculpture

The Out of Control of Compulsion (2020), Kwak experimented

with recording and expressing past paintings on each surface of the structure.

This experiment, he notes, was influenced by Auguste Rodin’s The Gates

of Hell, in which individual sculptures coalesce into an

architectural scene. Just as Rodin’s work transforms gathered figures into an

architectural landscape, Kwak’s cement cube consolidates fragments of past

paintings into a newly formed sculptural landscape.

Kwak Intan,

Movement 21-1, 2021, Resin, steel, stainless steel,

perforated plate, putty, acrylic paint, epoxy, wheels, 160×97×63cm ©Museumhead.

Photo: Junyong Cho

Kwak Intan,

Movement 21-1, 2021, Resin, steel, stainless steel,

perforated plate, putty, acrylic paint, epoxy, wheels, 160×97×63cm ©Museumhead.

Photo: Junyong ChoBeginning with his 2021 works, Kwak Intan

turned his attention to the movement within sculpture. He became interested in

the latent motion embedded in the myriad forms that compose the surfaces of

great masters’ works as well as his own earlier sculptures. His aim was to

translate the writhing visual energy of these otherwise static surfaces into

new sculptural forms.

For instance, Movement

21-1 (2021) originated from the imagined act of liberating the figure

from The Out of Control of Compulsion (2020) and

Person Sitting on the Gate of Hell (2020), sending it swiftly

elsewhere. While this work also references multiple sources, Kwak approached it

with greater freedom, immersing himself in tactile textures and the processes

of both dismantling and reconstructing form.

Installation view of 《Injury Time》 (Museumhead, 2021) ©Museumhead. Photo: Junyong Cho

Moreover, Movement 21-1

was presented alongside Kwak’s earlier works that referenced various art pieces

in the group exhibition 《Injury Time》 at Museumhead in 2021. In this context, the work reflects not the

external adoption of references, but an inner inevitability that permeates his

practice. As a result, his sculptures move beyond the mere assemblage of

remnants from the past, emerging instead as forms that yearn for new collisions

and trajectories of movement.

Kwak Intan, Child Sculptor, 2022, Mixed media ©Kwak Intan

Meanwhile, beginning in 2022, Kwak Intan’s ‘Child

Sculptor’ series follows his characteristic method of sequentially developing

works by referencing art historical imagery, contemporary visual culture, and

his own earlier pieces, while also expressing his desire to return to the

beginner’s mind of childhood, seeking freedom from established frameworks and

the constraints of reality.

In these works, Kwak recalls the childhood

sensation of playing with clay and immersing himself in the sheer joy of

making. As if transported back to that time, he treats the sculptural body

itself as a playground, unfolding his visual language with spontaneity and

freedom.

Kwak Intan, Child Sculptor (detail), 2022, Mixed media ©Seoul Museum of Art

The 2022 work of ‘Child Sculptor,’

presented in the group exhibition 《Sculptural Impulse》

at the Seoul Museum of Art in 2022, playfully re-references

the artist’s previous works. The lower body of this 3.7-meter-tall piece uses

the leg forms from When Legs Become Stairs, recast in resin

clay in a variety of colors as the main structural element, upon which the

artist unfolds the shapes and textures explored in earlier experiments.

In contrast, the upper body, which

underwent a different spatial and temporal process, was created by scanning a

portion of a small model that served as the starting point for the 2021 ‘Movement’

series and enlarging it through 3D printing.

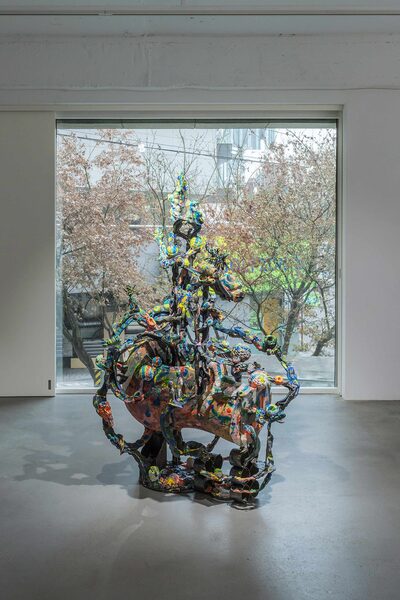

Kwak Intan,

Child Sculptor, 2024, Aluminum, urethane pain, 230x338x137cm

©Thiscomesfrom

Kwak Intan,

Child Sculptor, 2024, Aluminum, urethane pain, 230x338x137cm

©ThiscomesfromMeanwhile, the work presented in Sculpture

City, Seoul in 2024 combines multiple hand-formed emoticons and small figures

atop the sculpted full body in an improvisational yet intuitive manner,

creating a playful space where a variety of expressions and sensations

intermingle.

Like the images or information we encounter

through multiple channels in daily life, ‘Child Sculptor’—with its vivid mix of

colors and forms—evokes a tactile sense of liveliness. It is also a reflection

of the artist’s momentary emotions and sensations, embodied in the very process

of its creation.

Kwak Intan, Palette 3, 2022, Resin, acrylic, steel, 170x35x32cm ©K.O.N.G GALLERY

In the 2022 solo exhibition 《Palette》 at K.O.N.G GALLERY, Kwak Intan

presented the experimental ‘Palette’ series, in which sculptures themselves

serve as palettes. In this work, the artist shapes everyday concerns filling

the mind into clay by hand, attaching them to an underlying structure to create

varied, tactile contours. Following the flow of this tactility, small

additional sculptural elements are added and paint is layered on, ultimately

producing a new form that blends painting and sculpture.

Kwak Intan, Palette 2, 2022, Resin, water paint, acrylic, 134x51x32cm ©K.O.N.G GALLERY

The resulting Palette 2

(2022) evokes the blue stars that appear in Kim Whanki’s paintings. Looking

more closely at other works in the series, one can see Rodin’s busts and

various emoticons—each reimagined as small sculptural elements—that decorate

the pieces and add a playful dimension to the works.

Through this series of experimental

works—using sculpture itself as a palette for coloring—Kwak Intan reached a new

turning point, advancing beyond the sculptural approaches he had previously

explored. In subsequent works, he moved toward experimenting with sculpture as

a form that can endlessly expand, traversing between the real and the virtual

in a process of continual variation.

Kwak Intan, Intersection of Sculptures (조각 교차로) 1, 2023, Resin, PLA, cement, water paint, acrylic, iso pink, urethane foam, 95x63x151cm ©Kwak Intan

For example, in Intersection of

Sculptures 1 (조각 교차로 1) (2023), Kwak Intan

uses an unfinished bust as a pedestal while simultaneously transforming the

large openings in the bust’s facial area into passages and doorways through

which various sculptures intersect.

The organic lines that pass through the

bust reference a road intersection. The sculptures above the intersection

combine hand-shaped elements with pieces that were 3D-scanned and printed.

Through this process, the work becomes a space where sculpture, both real and

virtual, and forms from different spatial and temporal contexts intersect,

generating a sense of organic vitality.

Installation view of 《Shape and Shape》 (Ulsan Art Museum, 2025) ©Ulsan Art Museum

Kwak Intan describes sculpture as “space,

or a landscape.” Through the medium of sculpture, he mixes and reconstructs

various times and landscapes from his mind, creating a third, new landscape. He

treats this creative process as a playful arena, infusing his works with the

pure playfulness of art.

Kwak Intan’s practice redefines the meaning

of sculpture through the ways he records time and landscapes, his organic and

experimental forms, and his sculptural approach that embodies emotion and

symbolism. Recently, he has expanded his focus to audience interaction,

demonstrating that sculpture need not be a fixed form but can function as a

space that mediates experience and sensation, a dynamic presence.

“Sculpture is a passage through which

countless thoughts travel, and a playful space where diverse forms

converge.” (Kwak Intan, Artist’s Note)

Artist Kwak Intan ©Kwak Intan

Kwak Intan has a BFA in Environmental

Sculpture from the University of Seoul and an MFA in Sculpture from Hongik

University. His recent solo exhibitions include 《Shape

and Shape》 (Ulsan Art Museum, Ulsan, 2025), 《Palette》 (K.O.N.G GALLERY, Seoul, 2022), 《Sculpture Gate》 (space 9, Seoul, 2020), 《Unique Form》 (studio 148, Seoul, 2019),

among others.

He has also participated in numerous group

exhibitions, including the 7th Changwon Sculpture Biennale 《silent apple》 (Changwon, 2024), 《Circus Effect》 (Nakwon Sangga, d/p, Seoul,

2024), 《Shine That Eternal Silence Upon Us》 (GCS, Seoul, 2023), 《Sculptural Impulse》

(Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, 2022), 《Injury

Time 1》 (WESS, Seoul, 2022), 《Injury

Time》 (Museumhead, Seoul, 2021), and 《Against》 (Kimsechoong Museum, Seoul, 2021).

Kwak Intan was selected as a ‘Public Art

New Hero’ in 2021.

References

- 곽인탄, 인스타그램 (Kwak Intan, Instagram)

- 공근혜갤러리, 곽인탄 (K.O.N.G GALLERY, Kwak Intan)

- 비애티튜드, 놀이하는 창작, 유희하는 조각

- 퍼블릭아트, 터지고 비어져 나오는 뒤죽박죽의 자유

- 뮤지엄헤드, [서문] 인저리 타임 (Museumhead, [Preface] Injury Time)

- 서울시립미술관, [작품 설명글] 조각충동 (Seoul Museum of Art, [Artwork Description] Sculptural Impulse)

- 조각도시서울, [작품 설명글] 곽인탄 – 어린이 조각가 (Sculpture City, Seoul, [Artwork Description] Kwak Intan – Child Sculptor)

- 공근혜갤러리, [서문] 팔레트 (K.O.N.G GALLERY, [Preface] Palette)

- 울산시립미술관, [전시 소개] 모양과 모양 (Ulsan Art Museum, [Exhibition Overview] Shape and Shape)