Minseok Chi (b. 1990) works primarily with

the traditional medium of Korean painting to explore connections between

Korea’s traditional philosophy, shamanistic beliefs, and contemporary contexts.

In particular, he studies past shamanistic practices that linked the human

world with the realm of spirits through everyday elements such as stones,

trees, and mountains. As a contemporary artist, he reflects on the role of the

modern-day shaman—one who spiritually connects the diverse beings that inhabit

today’s complex society.

Minseok Chi,

Buddhas of Three Ages, 2014, Painting on wooden wall

installation, 250x350x190cm ©Minseok Chi

Minseok Chi,

Buddhas of Three Ages, 2014, Painting on wooden wall

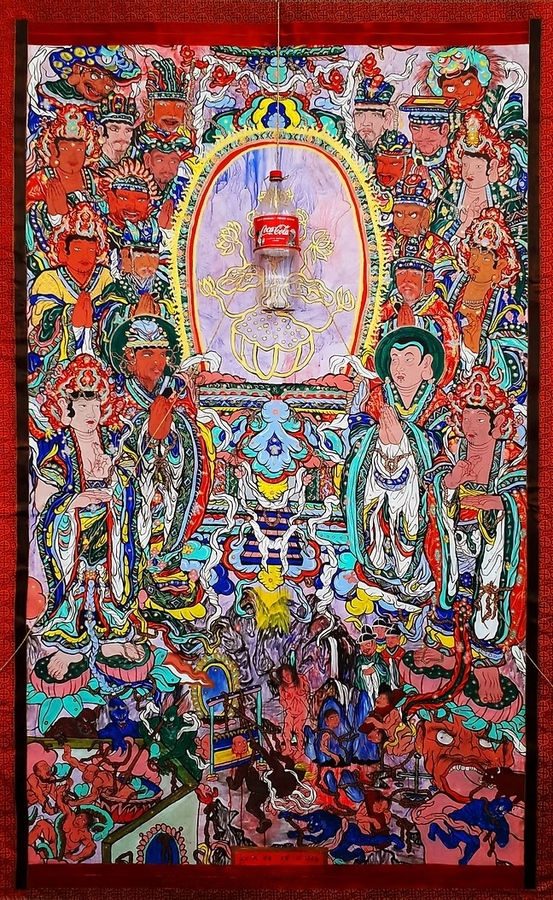

installation, 250x350x190cm ©Minseok ChiMinseok Chi’s early works focused on

contemporary reinterpretations of Buddhist iconography and formal structures.

In his ‘Buddha of Organs’ series (2014–2016), Chi reconstructed the figures of

Buddhas, heavenly beings, and other deities using anatomical imagery such as

human organs.

Within these works, organs like the heart

or lungs are seamlessly integrated into the traditional iconography of Buddhist

art, creating entirely new visual compositions. By merging the sacred forms of

the Buddha with the internal organs of the human body, the artist breaks down

the boundaries between divine and corporeal forms—visually embodying the

Buddhist philosophy that “all beings share the same essence.”

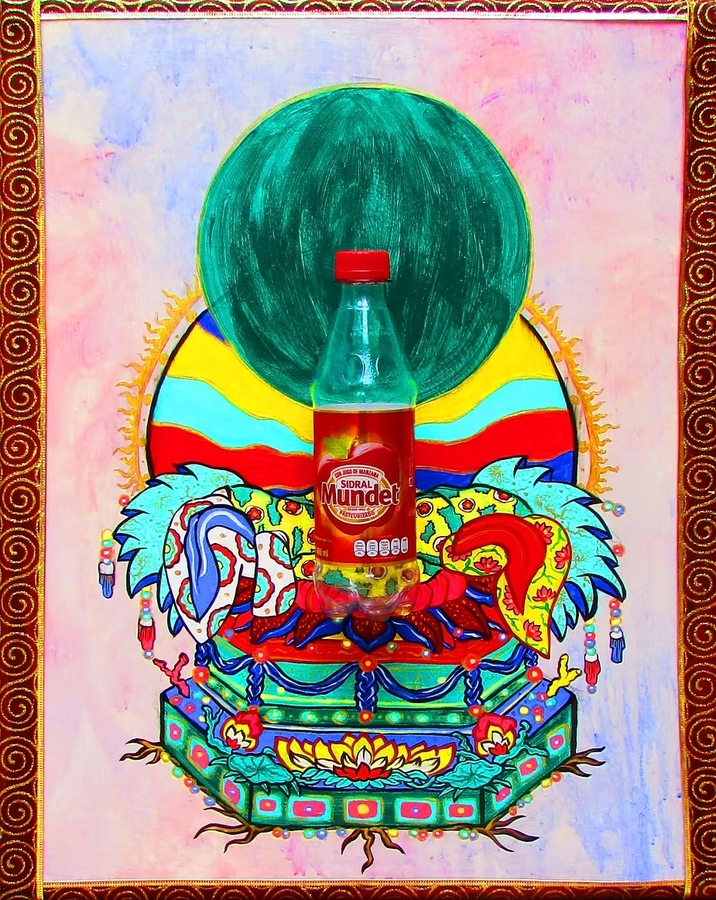

Minseok Chi, Buddha, 2015, Painting on canvas, object college, 55x43x8cm ©Minseok Chi

This philosophical and iconographic

reinterpretation of traditional religion—along with a blurring of

boundaries—continues in Minseok Chi’s ‘Buddha’ series (2015–2019). This body of

work also draws on diverse Buddhist iconography; however, rather than depicting

the Buddha in his traditional form, Chi places discarded objects such as

Coca-Cola bottles, shoes, toothpaste tubes, wine bottles, and disposable

containers in the Buddha’s place.

By positioning these mundane, overlooked

items—often considered worthless—in the sacred space typically reserved for

deities, Chi invites viewers to see these trivial objects from a renewed

perspective.

Minseok Chi, Seokkayeoraedo, 2019, Painting on canvas, object college, 250x130cm ©Minseok Chi

Through this work, the artist declares that “everything in the world—and all of us—are Buddhas” by offering a new way of seeing and questioning the ordinary. He states, “If we look at and feel the things around us—things we pass by thinking they have no value, even trash—with the eyes of a child, with fresh eyes, then everything can become beautiful, a reason for happiness, and an object of love.”

Minseok Chi, Coca-Cola, 2020-2023, Acrylic on cloth, 170x60cm ©Minseok Chi

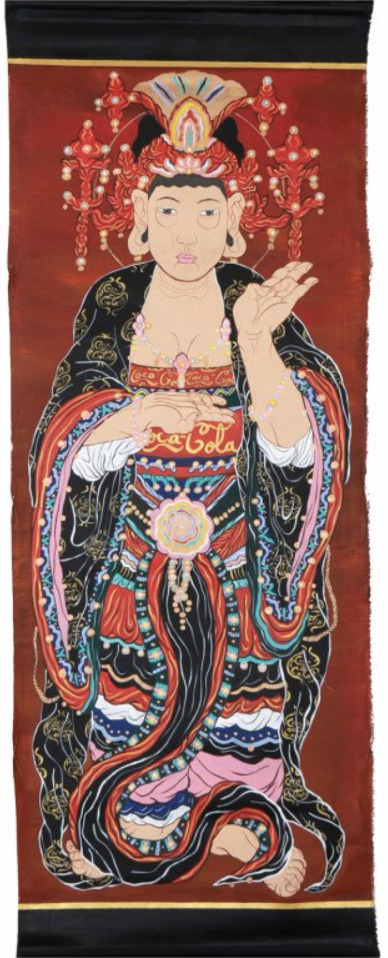

Since 2020, Minseok Chi has moved beyond

collaging everyday objects into religious iconography and begun portraying such

secular items as gods themselves.

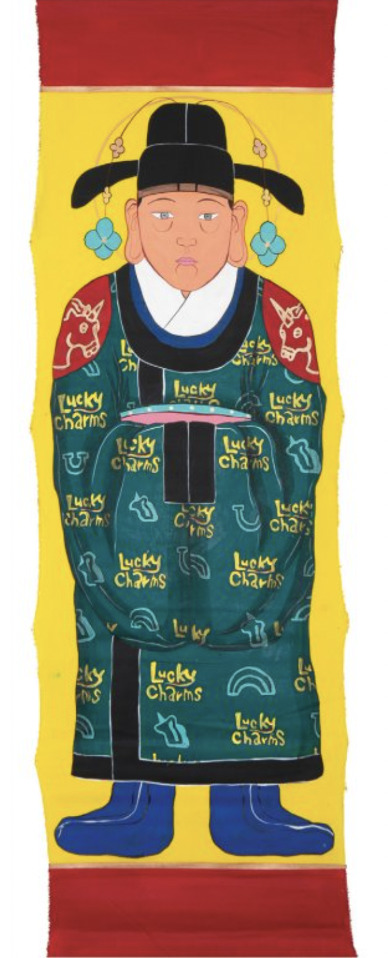

His portrait series ‘百八神衆道 The Way of the 108 Gods‘ (2020–2023) presents the results of his

uncanny observation of the values shared by society—such as reputation or

standard—stripped from things he has personally consumed: things he ate, drank,

wore, rode, or saw. Drawing on the format of tanghwa (幀畵)—traditional Buddhist scroll paintings depicting Buddhas or

bodhisattvas—these portraits depict globally consumed brands and products such

as Mickey Mouse, YouTube, Coca-Cola, Hermès, and Visa as anthropomorphic gods.

Minseok Chi, Hermès, 2020-2023, Acrylic on cloth, 170x60cm ©Minseok Chi

In today’s capitalist society, commodities

are often revered not merely as objects, but as if they possess supernatural

powers. For instance, the act of owning a luxury item such as an Hermès product

is often intended to signal one’s social status or personal value—an example of

how the symbolic and social meaning of a commodity is prioritized over its

practical utility. Karl Marx criticized this phenomenon as a kind of modern

superstition, coining the term commodity fetishism to describe how, under capitalism,

social relationships between people become obscured and are instead perceived

as relationships between things.

Minseok Chi, Rolex, 2020-2023, Acrylic on cloth, 170x60cm ©Minseok Chi

Minseok Chi began working on ‘The Way of

the 108 Gods’ by contemplating how today’s commodities—often regarded as

modern-day gods—might be represented if they were literally embodied as gods.

He explored how such objects, imbued with symbolic significance in the

capitalist era, could be expressed through religious iconography. To do this,

Chi assigned physical and human-like attributes to these symbols of

contemporary capitalism, transforming them into anthropomorphic deities, and

placed them within traditional religious frameworks to construct a new mythological

narrative.

Each of the 108 gods is accompanied by a

text, created by deconstructing Tao Te Ching, the

foundational text of Taoist philosophy by Laozi, and recomposing it in response

to the observation of 108 symbolic objects. In doing so, Chi deliberately

ignored the social meanings and symbolic layers attached to these objects in

contemporary culture, instead choosing to examine them with fresh eyes in order

to reveal their more essential nature.

Minseok Chi, Lucky Charms, 2020-2023, Acrylic on cloth, 170x60cm ©Minseok Chi

For example, when examining the American

cereal brand Lucky Charms, Minseok Chi writes:

“There are countless colors and lights

hidden in that rainbow. Only those who are close to the Dao can truly see them

and feel their real beauty. And when one truly experiences beauty, they can

live a long life.”

In this way, the artist dissects the

appearance of each object, subverts the brand’s business model through irony,

or recalls the sensory experience of consuming the product—then links these

impressions to phrases from Eastern philosophy.

Minseok Chi,

The way of the 108 gods dance , 2023, Performance video,

11min 2sec. ©Minseok Chi

Minseok Chi,

The way of the 108 gods dance , 2023, Performance video,

11min 2sec. ©Minseok ChiAs suggested by the number of

portraits—'108—The Way of the 108 Gods’ was, for Minseok Chi, a voluntary

spiritual practice aimed at confronting the essence of each object. And this

practice took on a playful, almost game-like quality. This spirit of playful

ritual extended beyond portraiture and evolved into a form of traditional

religious dance.

The religious ritual performance piece

The Way of the 108 Gods Dance (2023) was staged in the

symbolic frontline of capitalism: a department store. In this everyday

space—where countless goods are displayed and sold, and where culture is also

consumed—a dancer unfolded a bodily language of desire and longing for

happiness.

Curator Choi Goeun describes the ritual as

a moment where “the slippage between language and movement, and the dissonance

between object and stage, come sharply into focus.” She adds that the

awkwardness and unfamiliarity produced by this collision “becomes a key that

opens a gap between reality and habitual thinking.”

Installation view of 《百八神衆道 The way of the 108 gods》 (Sahng-up Gallery Euljiro, 2023) ©Sahng-up Gallery

In his 2023 solo exhibition 《The Way of the 108 Gods》 at Sahng-up Gallery

Euljiro, Minseok Chi presented a comprehensive display of 108 portraits,

scriptures, and ritual performances, transforming the exhibition into a space

of religious "play." The artist envisioned the gallery not just as an

altar dedicated to the 108 deities, but as a playful site where viewers could

imagine and engage in new forms of play grounded in his own performative acts.

Installation view of 《百八神衆道 The way of the 108 gods》 (Sahng-up Gallery Euljiro, 2023) ©Sahng-up Gallery

In this exhibition, the artist expanded the

doctrine of ‘The Way of the 108 Gods’ beyond the visual realm into auditory and

tactile experiences. The solemn flow of The Way of the 108 Gods

Music (2023) and the slow, fluid movements of The Way of the

108 Gods Dance (2023) harmoniously intertwined with the 108

portraits, organically connecting to transform the exhibition space in the

heart of Seoul into an unfamiliar, extraordinary place.

Through this playful space filled with

unfamiliar expressions and sounds, Minseok Chi hoped that visitors, upon

returning to their daily lives, would come to view all things as objects of

free observation and sources of joyful play.

Installation view

of 《Landscape of eight views of Dadaepo and Their Characters》 (Hongti Art Center, 2024) ©Hongti Art Center

Installation view

of 《Landscape of eight views of Dadaepo and Their Characters》 (Hongti Art Center, 2024) ©Hongti Art CenterThe following year, Minseok Chi presented

the solo exhibition 《Landscape of Eight Views of

Dadaepo and Their Characters》 (Hongti Art Center,

2024), showcasing a series of character paintings that extended the concept of

‘The Way of the 108 Gods.’ In this body of work, the artist created

hieroglyphic characters based on the forms of each of the 108 gods, developing

them into Chinese character-like symbols.

Chi then intertwined these characters with

the natural landscapes of Dadaepo’s “Landscape of Eight Views” (多大八景), located in Saha District, Busan, where the Hongti Art Center is

situated. The works explore the dissolution of boundaries between nature and

the artificial, probing possibilities for new harmonies.

Installation view of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber, 2024) ©Minseok Chi

In 2024, Minseok Chi’s solo exhibition 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 at

Chamber went beyond creating a one-dimensional iconography of the brand.

Through the Coca-Cola Goddess, he constructed a more multidimensional and

complex religious worldview unique to his practice.

The narrative of the Coca-Cola Goddess

begins with the world burning under an infinitely expanding sun, causing

everyone to lose their sight. The goddess is born from charcoal and grants a

dark shadow to those who cannot see, enabling humans to observe all things and

find their way. The fact that the Coca-Cola Goddess, opposing the sun, is born

from charcoal—an element sharing the sun’s attributes—relates to the

mythological concept of “identity fusion.”

This “identity fusion” in mythology

reflects the rationality of myths, showing that the contradictory existence—the

hated adversary—is continuously confronted and embedded within the human

unconscious.

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok Chi

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok ChiThe myth of the Coca-Cola Goddess also

incorporates the significant symbolic meaning of the number three, which holds

an important place in mythology. The three key elements in the Coca-Cola

Goddess myth—“charcoal,” “bottle,” and “legged herring”—correspond to the three-function

system.

The dual nature of the charcoal from which

the Coca-Cola Goddess was born represents divinity. The dark energy contained

in the bottle, which resists the sun, symbolizes martial power. Meanwhile, the

legged herring, always guarding the goddess, moves between water and land and

signifies divinity like the charcoal, while also symbolizing abundance, as

herrings have historically been a major food source for humans due to their

vast numbers.

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok Chi

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok ChiThe Coca-Cola Goddess, who once shared her

cool energy with people, sacrifices herself to block the ever-intensifying sun

and ascends to the sky. She sprinkles the dark energy from her bottle into the

heavens. The sun and the war deity, who once opposed the Coca-Cola Goddess,

come to a new mediation and each take turns appearing in the sky once a day,

thus giving birth to the night.

Through this myth, humanity regains its

subjectivity by seeing, owning, and understanding the night.

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok Chi

Installation view

of 《Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber,

2024) ©Minseok ChiMinseok Chi’s artistic world is not defined

by a fixed order, power, or capital; rather, it is grounded in a critical

awareness of a society rife with distorted values, alienation, and forgetting.

Against the imbalances created by extreme value biases and capitalism, he

explores the possibility of humans subjectively understanding the world through

“mediation.” The recurring theme of reclaiming subjectivity in his mythological

narratives aligns closely with this context.

For example, in the myth of the “Coca-Cola

Goddess,” the ever-growing sun symbolizes the absolute power and self-contained

reasoning of Western centrism and capitalism. The Coca-Cola figure, while a

product of capitalism, gains a complex meaning by being recontextualized within

the framework of Korean shamanism as a form of resistance.

Through this symbolic recontextualization,

Chi overturns Western prejudices, fantasies, and savior attitudes toward Korean

culture. In other words, he breaks down boundaries between tradition and

modernity, East and West, capital and faith, seeking new subjectivities and

cultural positions within these intersections.

Installation

view of 《Worlds Beyond Extraordinary》 (Gyeonggi

Museum of Modern Art, 2024) ©Monthly Art

Installation

view of 《Worlds Beyond Extraordinary》 (Gyeonggi

Museum of Modern Art, 2024) ©Monthly ArtMinseok Chi describes art as “a new kind of

play that can break down the serious games surrounding us.” He becomes the

master of a fictional play that weaves together contradictory and disparate

concepts, dissolving conditions of opposition and resistance. Chi joyfully yet

earnestly appropriates the vast concepts of the economic and cultural systems

around him within his own interpretive framework.

In this way, his art proposes an

alternative imagination where tradition and modernity, East and West, the

sacred and the profane coexist and harmonize, prompting reflection on the

essence of life and how we live.

“I think artists are somewhat like ancient

shamans. As a shaman of modern society, I create works while questioning how to

spiritually connect with the various everyday beings we see in our society.

These questions are then brought to life through new forms of play called

art.” (Minseok Chi, 2024 ARKO Young Artist Day Emerging

Artist Portfolio Exhibition: About Artist)

Artist Minseok Chi ©Saatchi Art

Minseok Chi majored in Oriental Painting at

Sungkyunkwan University and earned his Master’s degree in Fine Arts from the

National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). His recent solo exhibitions

include 《Ritual en Honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Arturo Herrera Cultural Foundation Museum, Pachuca, Mexico, 2025),

《Ritual en Honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola》 (Chamber, Seoul, 2024), 《Landscape of Eight

Views of Dadaepo and Their Characters》 (Hongti Art

Center, Busan, 2024), 《Ibsangjin-ui》 (Good Space, Daegu, 2024), 《The Way of the

108 Gods》 (Sahng-up Gallery Euljiro, Seoul, 2023), and 《Shinjungdo 神衆道》 (Samgaksan Art Lab, Seoul,

2022).

He has also participated in numerous group

exhibitions such as 《Miami Art Week》 (Gold Bust Motel, Miami, USA, 2024), 《Worlds

Beyond Extraordinary》 (Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art,

Ansan, 2024), 《Neo-Meta-Trans-》

(ARKO Art Center, Seoul, 2024), 《The Bureau of Queer

Art IV》 (Dama Gallery, California, USA, 2024), 《Traces of Time》 (Gallery A, Seoul, 2023),

the international Cervantino Art Festival 《Cruzando el

Pacífico》 (Guanajuato, Mexico, 2022), and 《Paisaje C》 (Museo de Arte de Pachuca,

Pachuca, Mexico, 2022).

In 2024, Minseok Chi was selected as a

resident artist at Hongti Art Center in Busan and was chosen for the Clavo

Emerging Artist Project in Mexico City. He also received the 13th Arte Abierto

Art Award from the Museum of the State Autonomous University of Mexico in 2018

and was shortlisted for the Tijuana Triennale in 2021.

References

- 지민석, Minseok Chi (Artist Website)

- 아르코미술관, 2024 ARKO 영아티스트데이: 작가소개 ⑧ 지민석 (ARKO Art Center, 2024 ARKO Young Artist Day: About Artist & Artwork ⑧ Minseok Chi)

- 대한민국 국제문화홍보정책실, 멕시코에서 선보인 일상과 불도의 경계에서 만나는 예술, 2017.09.20

- 갤러리 유니언, [서문] 자본주의 세계의 종말을 위한 새로운 신들 (Gallery Union, [Preface] Nuevos dioses para un fin del mundo capitalista)

- 상업화랑, [서문] 백팔신중도 (sahng-up Gallery, [Preface] 百八神衆道 The way of the 108 gods)

- 홍티아트센터, [보도자료] 다대팔경과 문자도 (Hongti Art Center, [Press Release] Landscape of eight views of Dadaepo and Their Characters)

- 임휘재, 코신제례의 합리성과 주체적 미래 상상