Grim Park (b. 1987) explores a range of

contemporary narratives—including queer perspectives—through the traditional

techniques of Buddhist art. His practice involves constructing new contemporary

narratives by merging, deconstructing, and recombining Buddhist iconography

with personal and social stories.

Through the contradictory questions that

emerge from this process, Park fundamentally challenges the binary concepts of

majority and minority that shape contemporary society.

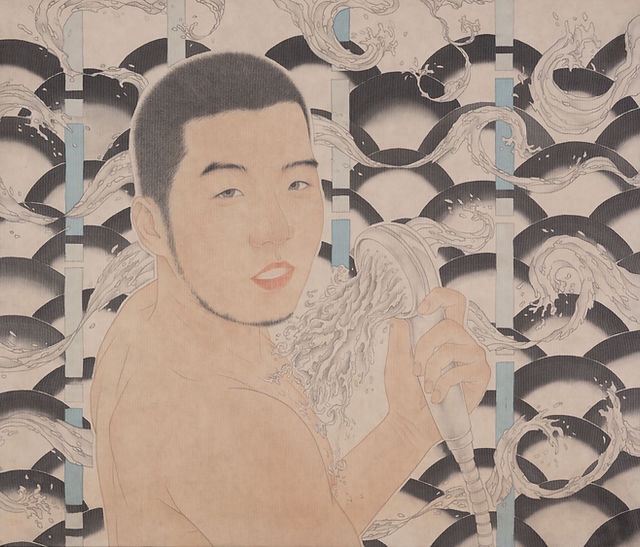

Grim Park, A man who came with an empty hand, 2015, Korean traditional paint on silk, 45.5x53cm ©Grim Park

Grim Park’s early series ‘Hwarangdo – A

Crowd of Beautiful Men’, which he began in 2015, beautifully idealizes gay men

using refined and delicate techniques rooted in traditional painting. The

motivation behind this body of work stems from the artist’s own self-loathing,

rooted in body-image insecurities. Observing the countless beautiful men on

social media, Park found himself admiring their self-love. This longing

eventually led him to depict their beauty—unfiltered narcissism and eroticism

alike—within his work.

To do so, Park turned to silk, the material

he felt most fluent in handling. He explains, “Silk is soft and

sensitive—qualities I associate with their beauty. Applying dozens of

translucent layers of pigment onto the fabric parallels the effort and labor

required to attain beauty itself.”

Grim Park, A man who came out of mentaiko cartoon, 2015, Korean traditional paint on silk, 45.5x53cm ©Grim Park

The artist portrayed male figures using

techniques derived from Goryeo Buddhist painting, which also shares methods

with royal portraiture. He employed the Yukrimunbeop (肉理文法) technique, in which the texture of skin is meticulously depicted

by drawing fine lines and dots along the facial muscles and contours using a

small brush.

The use of soft curves and the gradual

layering of delicate colors on silk serves to express the beauty of these men

in an exquisitely refined and sensitive manner.

Grim Park, Shimhodo - Vagabond, 2019, Korean traditional paint on silk, 230x145cm ©Grim Park

In his ‘Hwarangdo – A Crowd of Beautiful

Men’ series, Grim Park projected his autobiographical narratives and desires as

a queer individual. Beginning in 2018, however, he developed a new body of work

titled ‘Shimhodo (尋虎圖)’, or ‘The Search for the Tiger,’

in which he wove new queer iconographies and allegories by combining Buddhist

imagery with personal narratives. The series draws on the Buddhist tale

Shimwudo (尋牛圖), or The

Search for the Cow, a traditional Zen parable that depicts a young boy’s

journey to find his true nature, symbolized by the search for a cow.

In Park’s reinterpretation, however, the

boy is replaced by a tiger, and the cow by a bodhisattva. While the tiger is

widely perceived in Korean culture as a sacred and mystical creature, Park

references the Dangun myth, in which the tiger fails to become human and is

ultimately cast aside. The artist views this tiger as a figure with an

incomplete and unresolved identity.

Struggling with societal norms and his own

identity as both a queer person and an artist, Park adopted the tiger as his

persona, using it as a recurring symbol in his works to reflect his exploration

of queerness, otherness, and artistic selfhood.

Grim Park, Shimhodo - Chosen, 2018, Korean traditional paint on silk, 70x92cm ©Grim Park

In Shimhodo – Chosen

(2018), Grim Park replaces the beautiful gay men—figures he once admired—with

bodhisattvas, positioning himself as a tiger between them. Like his other

works, this painting employs the stylistic techniques of Goryeo Buddhist

painting. One of the bodhisattvas wears a translucent eye-covering and has

their eyes closed, visually echoing the character “Gan (柬)” in “Gantaek (간택)”, meaning “to cover the

eyes.”

The two bodhisattvas are seen placing a

rainbow-colored veil (sara)—traditionally worn by bodhisattvas—over the tiger,

symbolizing the artist himself. The rainbow veil directly references the LGBTQ+

flag, reinterpreting it through the lens of Buddhist iconography. This symbolic

gesture reflects the artist’s attempt to articulate his queer identity and

marginality through the visual language of Buddhist art, a genre itself

considered relatively peripheral within contemporary discourse.

Grim Park,

Shimhodo - Sunlight, 2022, Korean traditional paint on silk,

250x122cm, Shimhodo - Moonlight, 2022, Korean traditional

paint on silk, 250x122cm ©Grim Park

Grim Park,

Shimhodo - Sunlight, 2022, Korean traditional paint on silk,

250x122cm, Shimhodo - Moonlight, 2022, Korean traditional

paint on silk, 250x122cm ©Grim ParkMeanwhile, the paired works

Shimhodo – Sunlight (2022) and Shimhodo –

Moonlight (2022) portray the two bodhisattvas as Ilgwang Bosal

(Bodhisattva of Sunlight) and Wolgwang Bosal (Bodhisattva of Moonlight),

respectively, representing the dual nature inherent in all human beings. By

embodying both sun and moon, these figures address the ambivalence within human

identity.

This iconography questions the tendency to

fix a person into a single image based on first impressions—challenging binary,

stereotypical perceptions rooted in rigid human judgment.

Grim Park, Bel Ami, 2020, Korean traditional paint on silk, 130x130cm ©Grim Park

In his ‘Bel Ami’ series (2020–2021), Grim

Park presents depictions of collective sexual encounters among gay men,

approaching the subject purely from a queer perspective. In this body of work,

the artist intentionally removes the Buddhist iconography that had previously

been central to expressing his identity, revealing a desire to break away from

established visual conventions.

Rendered within square frames inspired by

Instagram’s interface, Park paints nude groupings of gay men engaged in various

erotic positions. The title “Bel Ami” carries layered meanings: first, it

references a well-known gay pornography label; second, it alludes to the

titular character of Guy de Maupassant’s novel—an ambitious man who capitalizes

on his beauty; and third, it can be read literally as “beautiful gay friends.”

Grim Park, Bel Ami_Entrance, 2021, Korean traditional paint on silk, 30cm (diameter) ©Grim Park

Another intriguing aspect of the ‘Bel Ami’

series is the use of the sara—a traditional veil worn by bodhisattvas—which, in

these scenes, functions to cover the genitals or sexual organs. Art critic Geun-jun

LIM noted, “What is realized through this sanctification of erotic imagery

(eumhwa) is a form of aesthetic sublimity—a search for noble value within the

erotic network of vulgar desire. In other words, it is an attempt to create a

new harmony between the sacred and the profane.”

Installation view of 《CHAM; The Masquerade》 (UARTSPACE, 2021) ©UARTSPACE

The solo exhibition 《CHAM; The Masquerade》, held at UARTSPACE in

2021, showcased works produced as part of the artist’s exploration of identity

through questioning and rethinking his existing artistic methods. Centered on

the theme of the “contemporary application and reinvention of traditional painting,”

the exhibition included the ‘Bel Ami‘ series, among others.

Among the works, Sad

Tiger (2021)—featuring the artist’s persona, the tiger—symbolically

represents the journey of searching for one’s identity. Divided into two

panels, the piece presents a close-up of a baby tiger’s eyes in one frame and

the tiger’s tail wrapped in a translucent black sara in the other.

Grim Park, Sad Tiger, 2021, Korean traditional paint on silk, each 각 27x110cm, Installation view of 《CHAM; The Masquerade》 (UARTSPACE, 2021) ©UARTSPACE

The image of the sara draped over the

tiger’s tail in this work draws inspiration from Indra’s net (indrajāla),

an allegorical concept from Buddhist philosophy. In Buddhist cosmology, Indra’s

net is a jeweled net suspended over the palace of Śakra

(Jeseokcheon), the guardian deity of the Buddhist teachings. This net, central

to the Huayan (Flower Garland) school of thought, symbolizes the interdependent

nature of all beings in the universe.

Just as each jewel in the net reflects and

is reflected by all others, endlessly connected, Park’s work embodies this

Buddhist principle in the realm of contemporary art. Through this visual

metaphor, the artist conveys a deep belief in the interconnectedness and

equality of all beings, presenting his art as a means of expressing the

infinite and reflective relationships among all forms of existence.

Installation view of 《虎路, Becoming a Tiger》 (Studio Concrete, 2022) ©Studio Concrete

Furthermore, in his 2022 solo exhibition 《虎路, Becoming a Tiger 》 held at

Studio Concrete, Grim Park presented a comprehensive narrative of his artistic

development. The exhibition’s title, “虎路 (Horō)”—meaning

“the tiger’s path”—reflects Park’s symbolic identification with the tiger as

his artistic persona. Through both the physical aesthetics of the tiger’s form

and the intangible aesthetics of its strength and courage, Park charts a

journey of overcoming his own self-loathing.

The exhibition traces a progression from

early works that idolized others—rooted in self-hatred—to pieces in which the

artist’s own identity begins to emerge. It captures Park’s autobiographical

path of personal transformation, while simultaneously expressing his deep

desire to be reborn as “Grim Park,” the artist.

Installation view of 《虎路, Becoming a Tiger》 (Studio Concrete, 2022) ©Studio Concrete

The overall structure of the exhibition is

composed of the ‘Shimhodo’ series, Zero–Cogitation–Samadhi,

The Tiger of Perfect Wisdom (Interracial), and the ‘Tasty

Tail (Penis)’ series, each addressing the themes of reincarnation,

self-realization, compassion, and polyamory, respectively.

Specifically, the ‘Shimhodo’ series

captures the fleeting moment and history of the artist’s rebirth as a

self—emerging through the dialectical narrative of the power dynamics between

subject and other. Zero–Cogitation–Samadhi traces the steps

toward nirvana through a profound awakening to the self. The Tiger of

Perfect Wisdom expresses a foundation of self-love built upon the

understanding and acceptance of one's fundamental human imperfection. Finally, ‘Tasty

Tail’ celebrates and explores the aesthetic pleasure and tension that arise

from social relationships rooted in that self-love.

Installation view of 《YES, My 로드 》 (THEO, 2022) ©THEO,>

Since then, Grim Park has gradually expanded the scope of his work by presenting the ‘Holy Things’ (2022) series, which combines contemporary narratives and imagery with traditional modes of expression, as well as the ‘Turning to the Darkside’ (2022) series, which explores dichotomous narratives and character reversals to reveal ambivalence.

Installation view of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEO

The 2024 solo exhibition 《44》 at Gallery THEO showcased the process of

layering and expanding past motifs through which the artist recognized and

affirmed himself within relationships.

The exhibition invited viewers to see not

only individual works but also the artist’s earlier pieces and older traditions

in a multidimensional relationship, encouraging a “layered viewing” to explore

what is repeated, varied, and what emotions or implications are conveyed.

For example, the show emphasized the

artist’s ongoing exploration of self-identity by intentionally layering,

mirroring, and overlapping past works and their interrelations, reinforcing the

visualization of his evolving identity.

Installation view

of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEO

Installation view

of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEOThe most striking self-aware image

presented in the exhibition appears in the tiger from the ‘Shimhodo’ series. In

the earlier ‘Shimhodo’ works, the artist often placed the tiger—identified with

himself—alongside the bodhisattvas. However, in 《44》, those figures have disappeared. Some pieces evoke a postscript

scene where the past artist (the tiger) has removed the surrounding

bodhisattvas.

In the absence of the bodhisattvas, the

tiger on the canvas becomes a symbol and form of self-awareness—one that

reflects inward, examining and reaffirming itself rather than relating to

others. For example, in Moon Play (日劇)

and Sun Play (月劇), the tiger,

adorned with the halo or aura typically depicted around the Buddha, appears to

attain enlightenment through meditation, reconciling the differing qualities of

its inner and outer nature.

Grim Park,

Return, 2024, Korean traditional paint on silk, 230x100cm, Installation

view of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEO

Grim Park,

Return, 2024, Korean traditional paint on silk, 230x100cm, Installation

view of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEOThe relatively large-scale works Return (回) (2024) and Wheel (輪) (2024), positioned at the center of the exhibition space, feature imagery reminiscent of the Shimwudo’s concept of “Inugumang (人牛俱忘)” — the simultaneous forgetting of both human and cow. These images clearly reveal the duality and complexity that permeate Park Grim’s work as a whole, while also highlighting its cohesion and expansiveness.

Grim Park,

Wheel, 2024, Korean traditional paint on silk, 230x100cm, Installation

view of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEO

Grim Park,

Wheel, 2024, Korean traditional paint on silk, 230x100cm, Installation

view of 《44》 (THEO, 2024) ©THEOThese works erase any surface-level

narrative of the present world or events occurring between the ox and the

herder—any incidents arising from their relationship—and, like the concept of

Inugumang in Shimwudo (which depicts a state of forgetting both the cow and

oneself, represented by a simple empty circle), they offer no clues for

interpretation beyond simple traces.

Such extremely minimal images, backgrounds,

and negative spaces support self-aware scenes that overcome dichotomies such as

“beginning and end, inside and outside, self and other, past and present,

tradition and innovation,” while also reflecting the overlapping and cyclical

nature of the spiritual quest.

Grim Park, Enigma 我尾, 2024, Korean traditional paint on silk, 120x40cm ©Grim Park

In the self-portrait Enigma (我尾) (2024), Grim Park appears within a fissure, even in a

torn state. This “appearance through tearing” can be understood as an image of

a different nature from past selves reliant on surrounding relationships or

marked by self-loathing and admiration of others.

Park’s work comprehensively embodies the

artist’s journey confronting Buddhist art traditions, queer identity, human

relationships, and past experiences and events. While passing through

autobiographical narratives, his practice expands into forms that allow diverse

reflections on today’s relationships with others and society’s binary

stereotypes.

Moreover, rather than unconditionally

following tradition, he explores and reinterprets prior precedents and rules in

his own unique way. His work, seen as a process of adaptation and renewal,

invites reconsideration and “confrontation” of contemporary contradictions

through traditional materials and concepts.

“Equality in Buddhism means that the

fundamental nature of all things and all phenomena in the world is equal and

uniform without discrimination. I want to convey that value in a new and

meaningful way.” (Grim Park, from an interview with Today

News)

Artist Grim Park ©UARTSPACE

Grim Park studied Buddhist art through an

apprenticeship system and graduated from the Department of Buddhist Art at

Dongguk University. His solo exhibitions include 《44》

(THEO, Seoul, 2024), 《虎路, Becoming a

Tiger 》 (Studio Concrete, Seoul, 2022), 《CHAM; The Masquerade》 (UARTSPACE, Seoul,

2021), and 《花郞徒 - a Crowd of beautiful men》 (Bul-il Museum, Seoul, 2018).

He has also participated in various group

exhibitions, including Minhwa and K-Pop Art Special Exhibition 《Worlds Beyond Extraodrinary》 (Gyeonggi

Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, 2024), 《It makes me a

sinner who is doing well》 (OCI Museum of Art, Seoul,

2024), 《PANORAMA》 (SONGEUN,

Seoul, 2023), 《The 22nd SONGEUN Art Award Exhibition》

(SONGEUN, Seoul, 2022), 《Korean

Traditional Painting in Alter-age》 (Ilmin Museum of

Art, Seoul, 2022), 《BONY》 (Museumhead,

Seoul, 2021), 《flags》 (DOOSAN

Gallery, New York, 2019), among others.

Park was selected as a finalist for the

22nd SONGEUN Art Award in 2022 and won the Absolute Vodka Artist Award in 2018.

His works are included in the collection of the Sunpride Foundation.

References

- 박그림, Grim Park (Artist Website)

- THEO, 박그림 (THEO, Grim Park)

- THEO, [서문] YES, My 로드 (THEO, [Preface] YES, My 로드 ),>,>

- 월간미술, 박그림: 불화에 투사된 정체성의 회화 – 유진상

- 비애티튜드, 간절히 바라면 이루어지는

- 투데이신문, ‘성소수자 불교미술가’ 박그림 작가 “아름다움 넘어 평등 그리고파”, 2021.05.19

- 임근준, 정월(井月) 박그림의 작업 세계 ; 단천한 인연조차 고귀한 음예의 빛을 발하는

- 스튜디오 콘크리트, [서문] 虎路(호로), Becoming a Tiger <서울> (Studio Concrete, [Preface] 虎路, Becoming a Tiger)

- THEO, [서문] 사사 四四 (THEO, [Preface] 44)