Mooni Perry (b. 1990), a Berlin-based

artist, has been exploring various allegories and discourses shaped by

sociocultural contexts. Among these, she has focused on the concept of

so-called "double-fallen" beings—those who belong to neither side of

binary categories such as A or B—and has visualized the lives of such

marginalized individuals through research-based video works.

Mooni Perry, And They Begged Repeatedly not to order them to go into the Abyss, 2019, Single-channael video, 17min 36sec ©Mooni Perry

In Mooni Perry’s work, the concept of the “double-fallen”

refers to those who have been marginalized twice—figures who are the outsiders

of the outsider. That is, she focuses on individuals who do not belong to

either A or B, and thus are rendered “disobedient” or “nonconforming.” Mooni

Perry views these disobedient existences as agents that disrupt the binary

boundaries constructed by society, revealing within them the potential for new

narratives.

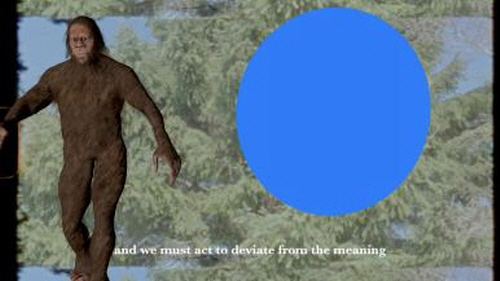

Grounded in this interest, the artist

weaves narratives that traverse and blur socially constructed borders. For

instance, her 2019 video work And They Begged Repeatedly Not to Order

Them to Go into the Abyss explores the intersectionality of veganism

and feminism, attempting to locate the gaps between things bound by fixed

meaning.

Mooni Perry,

And They Begged Repeatedly not to order them to go into the Abyss,

2019, Single-channael video, 17min 36sec ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

And They Begged Repeatedly not to order them to go into the Abyss,

2019, Single-channael video, 17min 36sec ©Mooni PerryIn this work, the artist shifts focus from

alterity as “the state of the other” to the other that already resides within

the self—an other who is both “you” and “I,” a presence that prevents the self

from remaining whole or coherent. Based on this broader notion of alterity, the

“other” in the work extends beyond human difference to include animal beings

such as pigs and sheep that appear throughout the piece.

The work not only prompts reflection on

coexistence with other species but also suggests that this process is far from

seamless or idealized. Rather, it is noisy, messy, and discomforting—resisting

romanticization.

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k, stereo

sound ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k, stereo

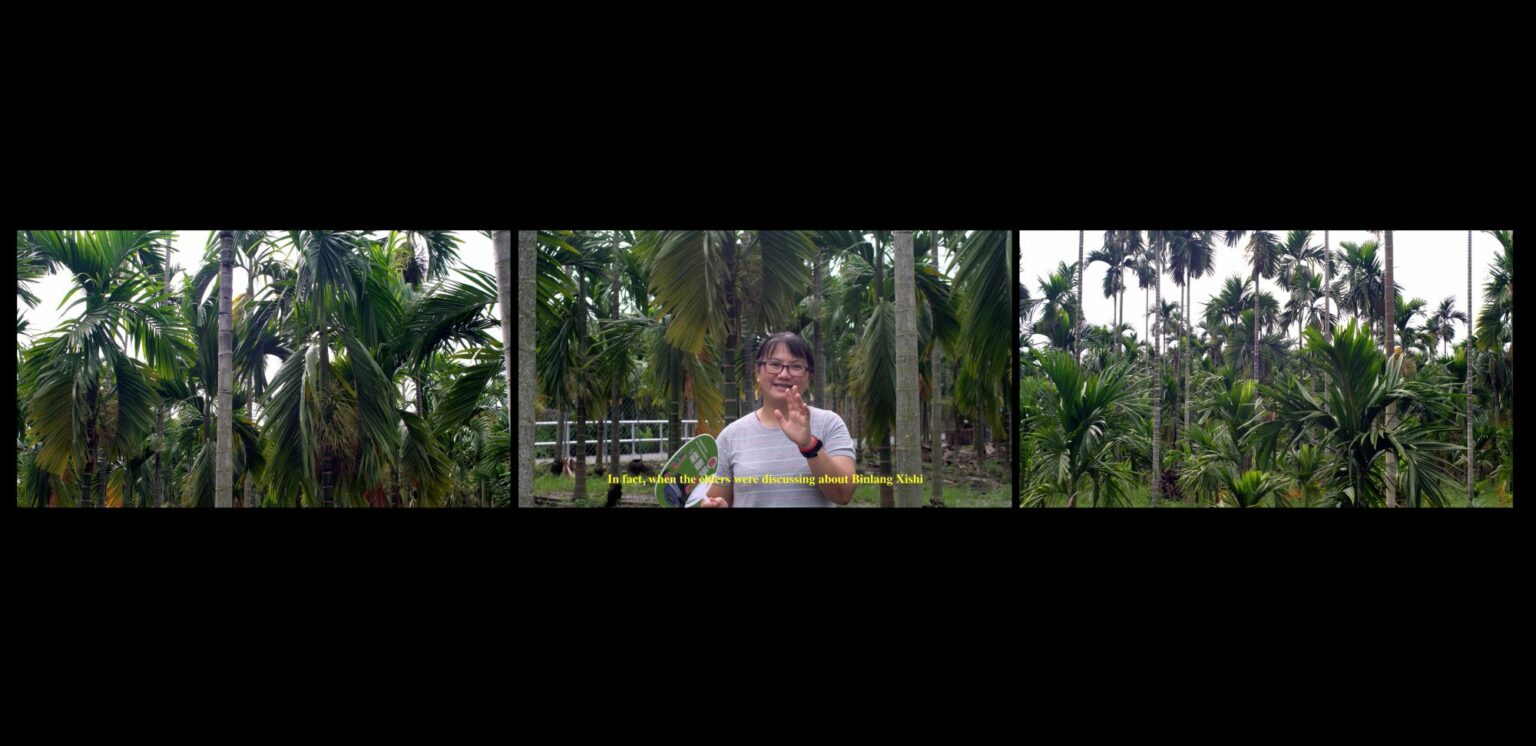

sound ©Mooni PerryIn her 2021 solo exhibition 《Binlang Xishi》 at CR Collective, Mooni Perry

explored allegories of contamination shaped by various socio-cultural contexts.

The video work Binlang Xishi (2021) centers on figures who

precariously exist on the margins of sex work.

The title of both the exhibition and the

work, Binlang Xishi, refers to young women who sell betel nuts (檳榔)—a tropical fruit with stimulant and mildly hallucinogenic effects.

Betel nuts have long circulated as a popular substance across Taiwan and East

Asia, and their energizing properties made them especially favored by male

manual laborers.

To attract more customers, binlang xishi

adopted provocative strategies, such as wearing revealing clothing and

operating from small roadside booths. However, after the sale of betel nuts was

outlawed in Taiwan in 2002, these women—already positioned on the threshold of

sex work—were pushed further to the fringes of visibility and legality.

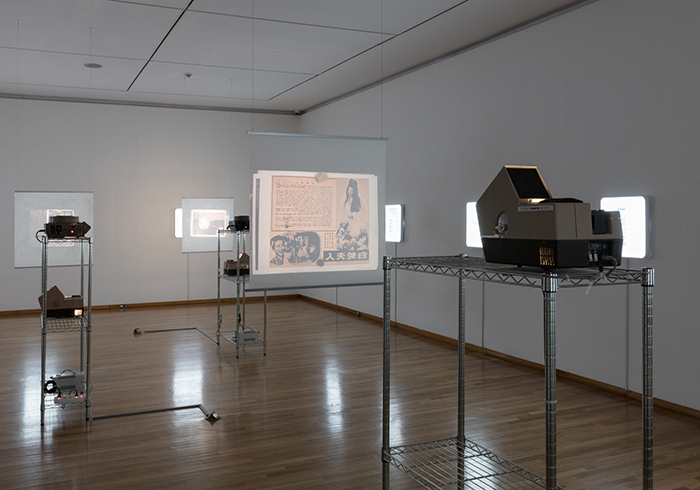

Installation view

of 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, 2019) ©CR

Collective

Installation view

of 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, 2019) ©CR

CollectiveThrough this work, Mooni Perry seeks to

address what she calls “stained beings.” The binlang xishi, who have fallen

twice—biologically and socioeconomically—from the standards of human

normativity, are easily cast as so-called “dirty beings.” In response, the

artist asks, “What is filth?” and, “Then what, exactly, is purity?” She

challenges the binary logic that underpins notions of cleanliness and

dirtiness, urging us to overturn and rethink these entrenched concepts.

The video is structured into three

chapters, each set in Korea, Taiwan, and Berlin. The first chapter, filmed in

Korea, opens with a pansori performance. The singer chants about “fallen

beings”—figures who drift in a suspended state, unbound by specific times or

places.

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi_chapter 1, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k,

stereo sound ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi_chapter 1, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k,

stereo sound ©Mooni PerryAmong the lyrics is a striking line:

“Floating in the sky, I looked down at my body—my feet had turned into sweet

potatoes, then corn, then winter melons and bottle gourds.” This imagery was

inspired by Taiwanese writer Li Ang’s novel Seeing Ghosts.

While reading the line “I hovered and looked at my body,” the artist drew a

parallel with the dissociative experiences reported by many sex

workers—specifically, the sensation of observing one’s own body from the

outside, as a symptom of psychological detachment.

In addition, the lyrics were informed by

historical accounts of sex work in Korea, weaving together narratives that

transcend time and geography. They summon the lives of those long labeled

“dirty” or “fallen,” suggesting that such existences have always persisted, in

different forms and contexts.

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi_chapter 2, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k,

stereo sound ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

Binlang Xishi_chapter 2, 2021, 3-channael video, VHS/8,16mm/4k,

stereo sound ©Mooni PerryIn the second chapter, filmed in Taiwan,

the narrative of the Binlang Xishi unfolds in earnest. The video introduces two

types of laborers within the betel nut industry: one is a farmer who cultivates

the betel nuts, and the other is a service worker who sells them—the Binlang

Xishi.

The farmer speaks about the history of

“dirtiness” associated with betel nuts, lamenting the political and social

regulations that have imposed a stigma upon the fruit. Though she does not say

it directly, the Binlang Xishi likely represents, in his eyes, a “disruptive”

presence that casts a shadow over the integrity of her labor.

Meanwhile, the two Binlang Xishi who run a

roadside stand confront the perceptions that surround them, posing the

following questions:

“Are Binlang Xishi unruly, impure beings?”

“And if so—why does that matter?”

Installation view

of 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, 2019) ©CR

Collective

Installation view

of 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, 2019) ©CR

CollectiveIn the video, Mooni Perry neither advocates

for nor rejects any party based on binary notions of right and wrong. Instead,

she presents the multitude of intertwined narratives that surround betel nut

culture. Her approach to subverting the concept of “dirtiness” lies in

identifying the gaps—those spaces that cannot be fully explained or contained

by the binary that divides unsettling beings, including the Binlang Xishi.

The artist believes that these gaps—where

various stories intersect and continuously slip—open up the possibility of a

leap toward somewhere undefinable, beyond fixed categories. As a metaphor for

this idea, Mooni Perry includes scenes of the Binlang Xishi in the video subtly

smiling, as if privy to a secret, while passing through a “portal.” She also

installs a large blue hole that fills an entire gallery window, symbolizing

this threshold.

These twice-fallen beings—those who have

“fallen” both socially and biologically—enter a fragmented space beyond the

portal, where there is no longer a top or bottom, no descent from cleanliness

to filth. In this realm, the “fallen” no longer need to arrive anywhere, nor

must they struggle to shed the stigma of impurity.

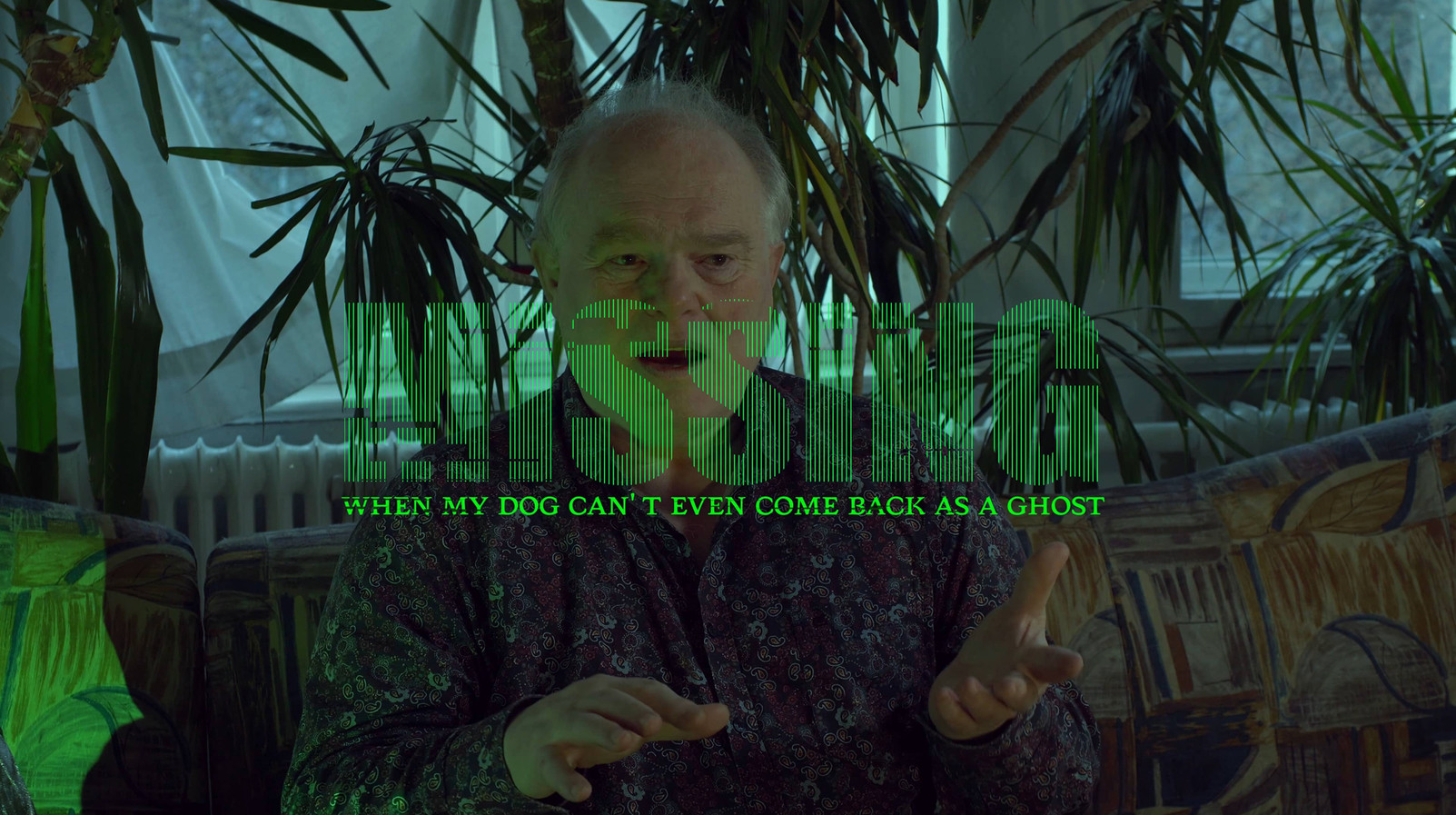

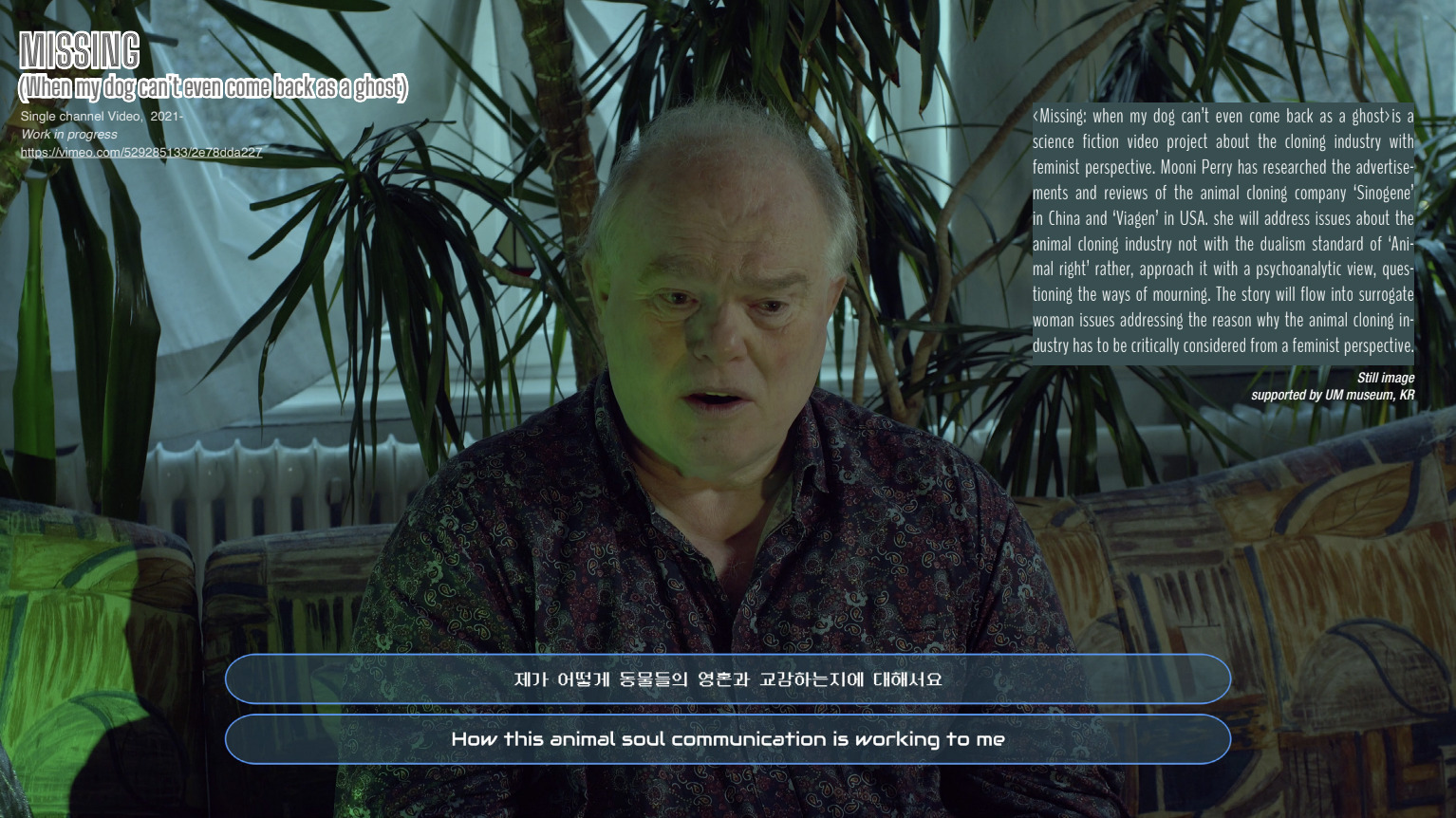

Mooni Perry,

Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2021,

Single-channael video, 5min 20sec. ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2021,

Single-channael video, 5min 20sec. ©Mooni PerryFollowing this trajectory, Mooni Perry

initiated the video project ‘Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a

Ghost’ (2021-), which explores the subject of pet cloning through the lens of

loss and mourning, and further links the issue to surrogate labor, calling for

a feminist reexamination of animal cloning practices.

While discussions surrounding the animal

cloning industry often revolve around ethical debates and animal rights—framed

in binary terms of support or opposition—Mooni Perry instead approaches the

topic through the emotional process of mourning and the concept of

reincarnation.

Mooni Perry,

Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2021,

Single-channael video, 5min 20sec. ©Mooni Perry

Mooni Perry,

Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2021,

Single-channael video, 5min 20sec. ©Mooni PerryRegarding pet cloning, the artist views it

as an “artificial stitching” carried out to overcome the sense of loss and

emptiness that comes from losing a beloved being. This psychological response

raises questions about whether such artificial acts can truly mend the

cracks—the ruptures in the world—and whether they even need to be mended at

all.

Furthermore, the artist contemplates where

the soul goes if the body of the lost being can be cloned. Focusing on Buddhist

perspectives on death and the afterlife, the artist is particularly interested

in the concept of the “bardo” (中陰身)—a spirit that

neither enters the realm of the dead nor fully departs from this world, stuck

in an intermediate state due to an inability to accept death and thus unable to

enter the cycle of reincarnation.

This bardo, a spirit existing between life

and death, is metaphorically linked to cloned pets who, despite having

completed their life, remain tethered to this world through the artificial

stitching of biological replication.

Mooni Perry, Research with Me, Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2022, Reading script, light box, magic lantern, Dimension variable, Installation view of 《2022 KUMHO YOUNG ARTIST 2》 ©Kumho Museum of Art

Furthermore, Mooni Perry points out that

the animal cloning industry is one that relies heavily on women’s bodies to

function. This industry requires numerous female bodies for the sake of a

single life, and in order to achieve a perfect clone, countless lives must be

born consecutively and then sacrificed.

The artist draws attention to the fact

that, if these beings involved in animal cloning were human, the clients

commissioning the clones would be socially and economically privileged

individuals deemed worthy of replication, whereas the bodies of surrogate

mothers are regarded as “consumable, replaceable necropolitical bodies”—that

is, entities subjected to the politics of death and life.

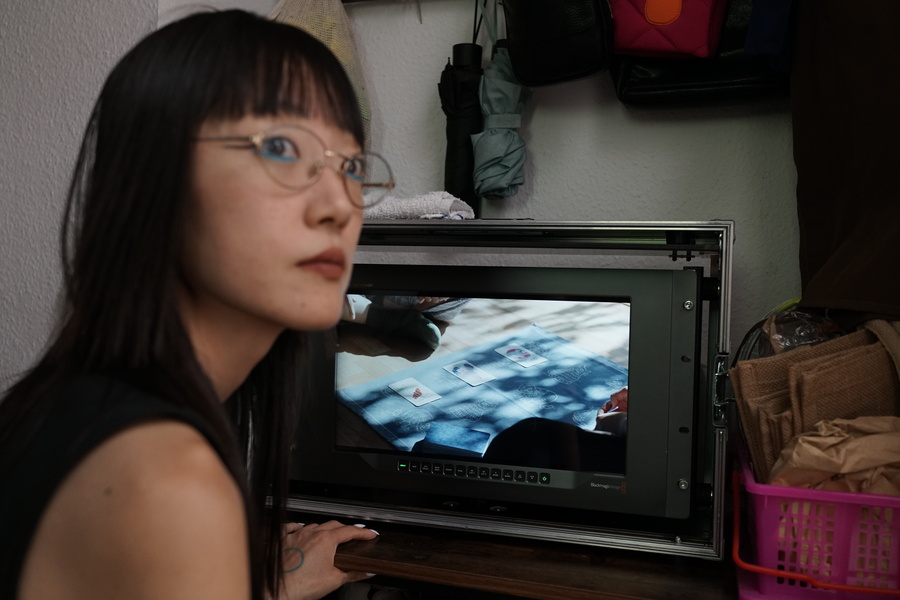

Mooni Perry, Research with Me, Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost, 2022, Reading performance, Dimension variable, Installation view of 《2022 KUMHO YOUNG ARTIST 2》 ©Kumho Museum of Art

In 2022, at the Kumho Museum of Art’s

exhibition 《2022 KUMHO YOUNG ARTIST 2》, Mooni Perry presented a work titled Research with Me,

Missing: When My Dog Can’t Even Come Back As a Ghost (2022). This

piece combined a performance of script reading and sound based on research

materials about the animal cloning industry, along with visual archival

documents.

Comprising video, performance, and archival

installation, the work intersects themes of disappearance and mourning,

differing ontologies of the body, and stories related to reincarnation with the

cloning industry. By linking this piece to the earlier work Binlang

Xishi, Mooni Perry reveals overlapping points and the complex

entanglement of multiple concepts between the two projects, exposing gaps that

cannot be fully explained within a binary discourse.

Subsequently, Mooni Perry developed this

project into an East Asian-style fantasy narrative. The artist questions the

connection between non-human entities and gender found within the element of

“fantasticality,” which plays a significant role in classical East Asian

literature. Moving between themes of disappearance, cloning industry, and

religious reincarnation, the artist explores the bizarrely expanding boundaries

and possibilities of the “self.”

Mooni Perry, EL, 2025, Single-channel video, color, sound, 34min. ©MMCA

At the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, currently hosting the exhibition 《Young Korean Artist 2025》, Mooni Perry is

presenting a short fiction film titled EL (2025). This video

project, created following research and filming conducted on-site in China, is

based on research about Manchuria during the Japanese colonial occupation.

The project centers on the stories of women

from Joseon who migrated there by force or choice but were ultimately unable to

return to their homeland. Shot at the Liaoning Hotel (formerly the Yamato

Hotel) in Shenyang, China, a site closely associated with the establishment of

Manchukuo, the film overlaps the reality and dreams of two protagonists,

evoking the past and present of the people from Joseon in Manchuria.

Mooni Perry,

EL, 2025, Single-channel video, color, sound, 34min. ©MMCA

Mooni Perry,

EL, 2025, Single-channel video, color, sound, 34min. ©MMCAWhile not driven by a specific storyline or

direct historical recounting, the film conveys the weight of a history in need

of recontextualization through its temporally saturated setting, the Liaoning

Hotel, and the protagonists, who resist stereotypical depictions of Asian women

in the modern era. Moving between past and present, dream and reality, Mooni

Perry probes the complex strata of history and identity.

Mooni Perry has conducted works based on

research into Asian identity as a whole, including feminism, Taoism and

tradition, and East Asian futurism. The artist weaves seemingly unrelated,

fragmented elements vertically and horizontally to create a unique narrative.

Her works feature beings that cross various boundaries and gaps, reminding us

that the world we live in is a complex and hybrid place full of cracks that

cannot be fully explained by simple binary logic.

“Within the themes I explore, what

can be called ‘gaps’ or ‘boundaries’ are very important. (…) When the

mainstream defines A, and some existence slips away from A, it settles as B.

But what I am truly interested in are those beings who slip once again from

B.

I am fascinated by those ‘unsettling

beings’ who are neither A nor B. I believe these beings become mechanisms that

disrupt the smooth functioning of both A and B. And I think it is precisely

within this unruliness that truly new stories begin.” (Mooni Perry, from an interview with AliceOn)

Artist Mooni Perry ©MMCA

Mooni Perry graduated from the Department of Painting at Hongik University and

completed her master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in the UK. Currently

based in Berlin, she has been running the platform AFSAR since 2021 with

multinational colleagues, sharing various research and creative activities.

Her

solo exhibitions include 《Missings: From Baikal to Heaven Lake, from Manchuria to

Kailong Temple》

(Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, 2024–2025), 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, Seoul, 2021), 《Mooni Perry》 (Bureaucracy Studies,

Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020), and 《Transversing》 (Post Territory Ujeongguk, Seoul, 2019).

She

has also participated in numerous group exhibitions such as 《Young Korean Artist 2025》 (National Museum of Modern

and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2025), 《Double:Binding:World:Tree》 (Post Territory Ujeongguk,

Seoul, 2024), the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul,

2023), 《The

Fable of Net in Earth》 (ARKO Art Center, Seoul, 2022), and 《2022 KUMHO YOUNG ARTIST》 (Kumho Museum of Art,

Seoul, 2022).

References

- 무니페리, Mooni Perry (Artist Website)

- 이상엽, [서문] 살아 있는 관계 (Rhii Sangyeop, [Preface] Living Relation)

- 앨리스온, [인터뷰] 불온한 존재들에 대하여 Part 1: 무니페리 Mooni Perry, 2022.06.27

- 탈영역 우정국, 무니페리 개인전_횡단 (Post Territory Ujeongguk, Monni Perry Solo Exhibition_Traversing)

- 씨알콜렉티브, [서문] 무니페리 개인전: 빈랑시스檳榔西施 (CR Collective, [Preface] Mooni Perry Solo Exhibition: Binlang Xishi 檳榔西施)

- 금호미술관, 2022 금호영아티스트

2부 (Kumho Museum of Art, 2022 KUMHO

YOUNG ARTIST 2)

- 아르코미술관, 땅속 그물 이야기 (ARKO Art Center, The Fable of Net in Earth)

- 탈영역 우정국, 이중:작동:세계:나무 (Post Territory Ujeongguk, Double:Binding:World:Tree)