Disappearing

Artists, Unrecorded Legacies

In contemporary

Korean art, one fact stands out: despite countless exhibitions and projects held

every week, very few artists have an official website

that documents their practice in a structured and lasting way.

Lee Ufan as featured on the gallery’s website / Screenshot from

Whitestone Gallery’s official webpage

Lee Ufan as featured on the gallery’s website / Screenshot from

Whitestone Gallery’s official webpageEven Lee

Ufan, one of Korea’s most internationally recognized artists, has

no personal website and no Catalogue Raisonné of his

work. Neither Park Soo-keun nor Lee Jung-seop—two of Korea’s most revered

modern masters—have one. This absence is telling.

Search online,

and you will find fragmented gallery pages or old press clippings, but rarely a

coherent system through which one can read an artist’s body of work.

The few websites that do exist are typically limited to exhibition schedules or

short bios, with low-quality images and little to no critical or research material.

As a result, many artists’ practices are reduced to “image

fragments” floating through SNS feeds, eventually fading without

a trace.

SNS Is

Ephemeral, the Web Endures

Screenshots of Korean artists’ Instagram

pages / Photo: Kookmin Ilbo

Screenshots of Korean artists’ Instagram

pages / Photo: Kookmin IlboMany Korean

artists are now active on Instagram. They post new works, share studio scenes,

and interact with audiences in real time.

But this

visibility is surface-level and short-lived. Feeds

flow endlessly, algorithms forget, and yesterday’s post becomes invisible. SNS

shows the present, but a website preserves the continuum.

These two platforms are not in competition; they must exist in tandem—social

media for immediacy, and the website as a foundation for permanence.

Only when SNS activity is anchored on a robust web platform does an artist’s

message transcend exposure and evolve into influence.

The Website as

a Creative Medium of Lifelong Record

A website is not

a marketing tool. It is a creative medium through

which an artist documents their world and situates themselves within time.

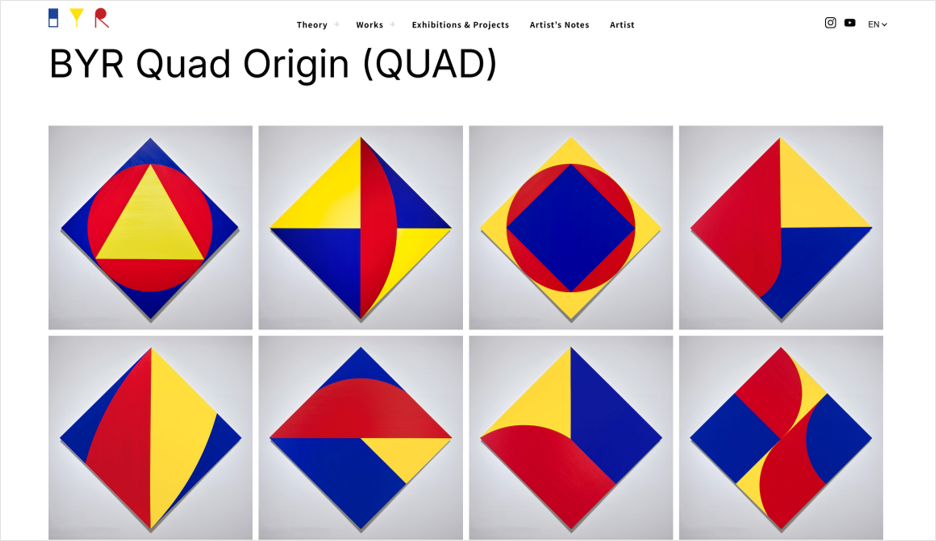

Screenshot of artist Heejo Kim’s website (heejokim.com)

The site presents the artist’s theoretical framework, statement, and works in a well-organized structure, available in both Korean and English.

A strong website

is not a gallery of images but a system of language—one that reveals the artist’s

thinking, evolution, and aesthetics at a glance.

It should include

complete image archives, exhibition histories, artist notes, critical texts,

installation views, interviews, and contextual information that traces the

making of each work.

When this

documentation is sustained, the website transcends the portfolio and becomes a <b>living Catalogue Raisonné—a

framework that not only demonstrates artistic excellence but naturally leads to

recognition, research, and promotion.

The Absence—and

Meaning—of the Catalogue Raisonné

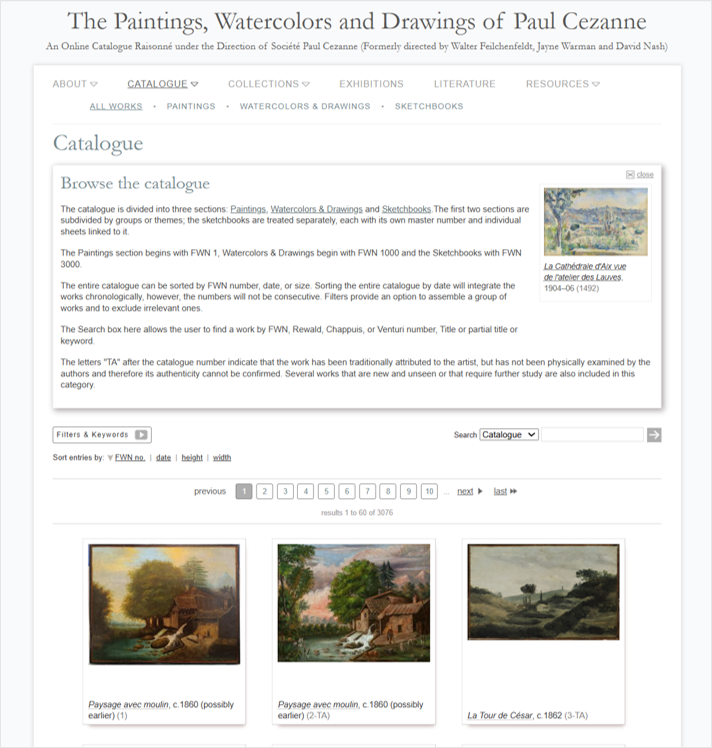

Digital Catalogue Raisonné featuring the complete works of Paul Cézanne

/ Source: Screenshot from https://www.cezannecatalogue.com

Digital Catalogue Raisonné featuring the complete works of Paul Cézanne

/ Source: Screenshot from https://www.cezannecatalogue.comA Catalogue

Raisonné is a scholarly, chronological record of all known works

by an artist, including dimensions, materials, provenance, exhibitions, and

literature.

It is not a list, but a proof of existence—a document

that anchors an artist’s authenticity and secures their place in art history.

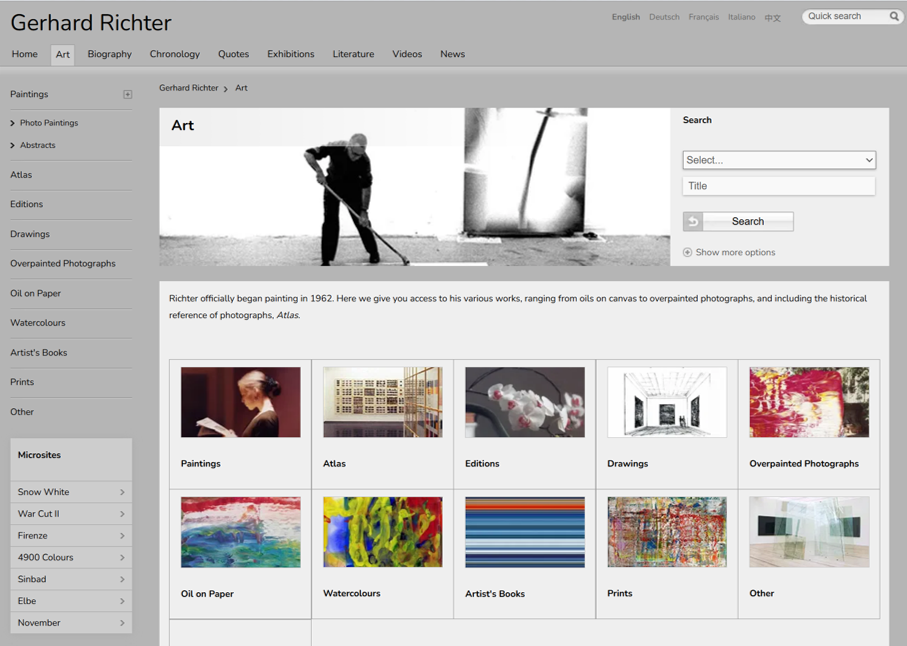

Main page of Gerhard Richter’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.gerhard-richter.com

Main page of Gerhard Richter’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.gerhard-richter.com “Art” menu page of Gerhard Richter’s Online Catalogue Raisonné /

Source: https://www.gerhard-richter.com

“Art” menu page of Gerhard Richter’s Online Catalogue Raisonné /

Source: https://www.gerhard-richter.comArtists like Paul

Cézanne, Francis Bacon, Jeff Koons, and Gerhard Richter

have built online catalogues that do far more than display images. They

establish a system that allows for research, verification, and transmission.

Because these structures exist, their art continues to live—beyond markets,

beyond generations, beyond mortality itself.

Francis Bacon’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.francis-bacon.com

Francis Bacon’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.francis-bacon.comKorean artists,

by contrast, have works but lack the records to prove them.

This absence makes Korean art appear transient—“existing only in

the present.” It shortens the perceived depth of its

history on the global stage.

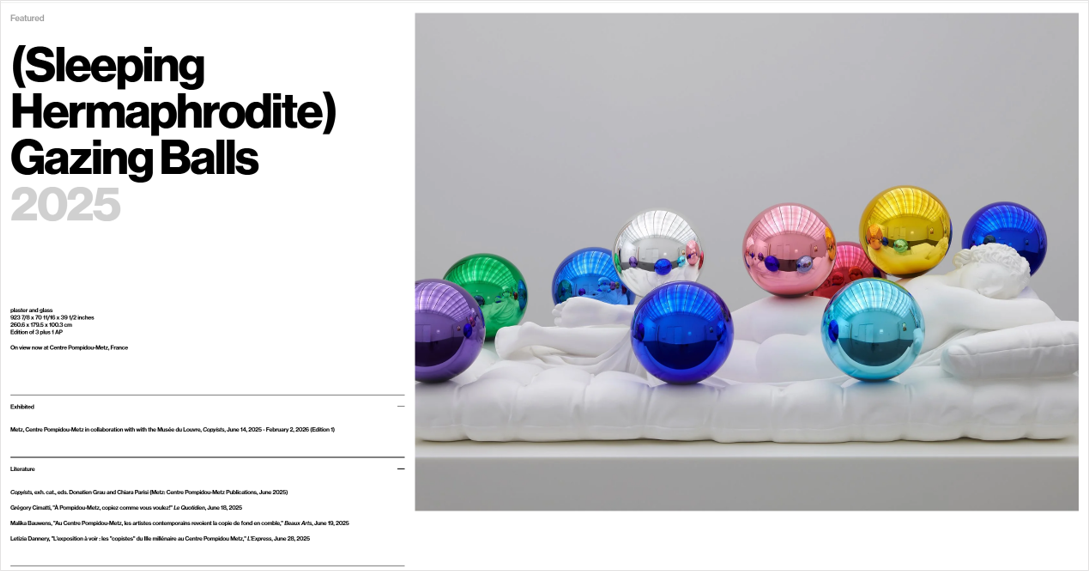

Jeff Koons’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.jeffkoons.com

Jeff Koons’s Online Catalogue Raisonné / Source: https://www.jeffkoons.comIn the lower-left section, the work details include references to exhibitions, catalogues, and publications in which the piece has been featured.

In South Korea, not

a single artist has produced an officially recognized Catalogue Raisonné.

This is a shocking fact, and it reveals not a lack of funding or institutional

support, but the deeper absence of a recording culture—a

failure to see documentation as an integral part of creation itself.

Structural

Deficiency in Korean Art

Korea’s art

ecosystem remains exhibition-centered. A few

catalogues, postcards, or press releases often constitute the entire record of

a show.

Once the

exhibition ends, materials scatter or lose meaning. Even public institutions

lack standardized artist databases.

Within a market-dominated system, artists have little digital sovereignty and

no stable channel through which to document their own narratives.

Korean art thus

continues to be consumed as a sequence of isolated events, rather than a

connected continuum. This is not a matter of publicity—it is a structural flaw that

threatens the historical continuity of Korean art itself.

Digital

Infrastructure Is the Starting Point of Global Reach

For Korean art to

take root globally, building a recordable, standardized

infrastructure must come before international exhibitions.

An artist platform that meets global standards—where data, metadata, and

archives are reliable and verifiable—is no longer optional but essential.

With such

foundations, artists can articulate their worlds proactively and intelligibly, and

their work will remain accessible to future scholars. This is the true

beginning of global presence.

Art Begins in

Creation, but Is Completed Through Record

Art is born in

the moment of creation, but it achieves permanence through record. Social media

may testify to the present, but only a website preserves history.

A website is not

a repository of works; it is the linguistic and historical map

of an artist’s existence—a structure that verifies, preserves, and extends

their art through time.

For Korean

artists to survive, evolve, and truly engage with the world, they must first

build the language and infrastructure that allow them

to record and interpret their own universes—a platform that stands as both

archive and agency, replacing the functions of gallerists, managers, and

promoters.

A person leaves a

name; an artist leaves their work. But unrecorded art disappears.

An artist’s website is not a digital accessory—it is the most

fundamental and ultimate medium through which a life in art endures, transmitted

to history and to the generations that follow.